by Maria McFadden Maffucci

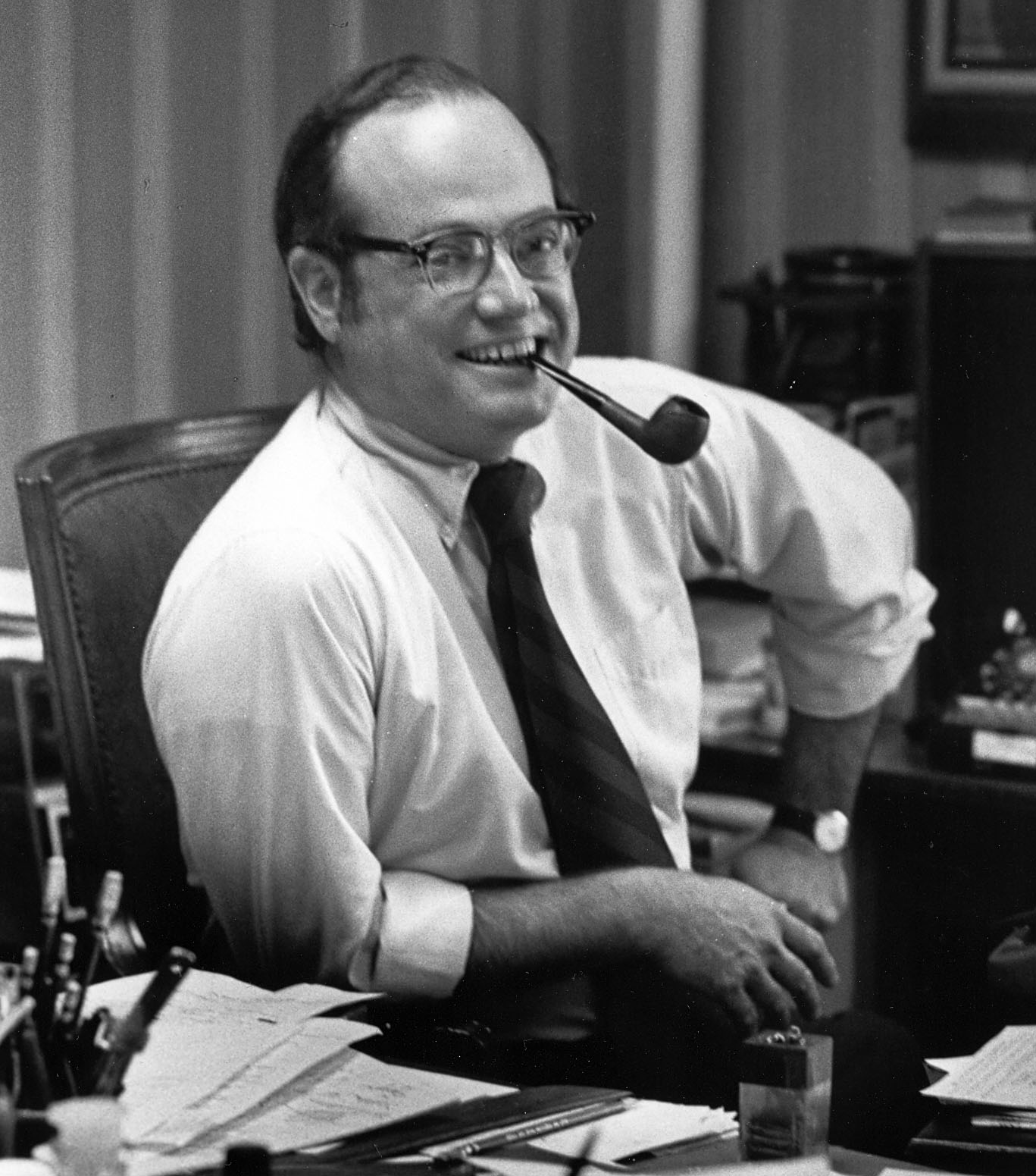

My father, James P. McFadden,“J.P.”, as he was called, came to New York in the late 50’s from Ohio, where he was a newspaper reporter. Being a fan of William F. Buckley Jr.’s 1951 book, God and Man at Yale, J.P. looked up Mr. Buckley in New York, and soon signed on at his new magazine, National Review.

A committed conservative, J.P. remained at National Review for over thirty years, building its circulation through successful direct-mail campaigns and eventually becoming Associate Publisher. But in 1973, his life changed. On January 23rd, while on vacation in Florida, he bought a copy of the New York Times, whose front page announced the shocking news of the day before: the passage of Roe v. Wade. J.P. sat and read the whole decision. He recalled later that it was “a day-long road to Damascus for me. I hadn’t realized these kinds of things were going on. I hadn’t realized that anyone was making these arguments, that the Supreme Court of the United States could put the moral suasion and moral power of this country behind killing babies.”

A committed conservative, J.P. remained at National Review for over thirty years, building its circulation through successful direct-mail campaigns and eventually becoming Associate Publisher. But in 1973, his life changed. On January 23rd, while on vacation in Florida, he bought a copy of the New York Times, whose front page announced the shocking news of the day before: the passage of Roe v. Wade. J.P. sat and read the whole decision. He recalled later that it was “a day-long road to Damascus for me. I hadn’t realized these kinds of things were going on. I hadn’t realized that anyone was making these arguments, that the Supreme Court of the United States could put the moral suasion and moral power of this country behind killing babies.”

J.P. realized that his journalistic and promotional skills could now be used to defend the unborn. In 1973, he set up the Ad Hoc Committee in Defense of Life, a pro-life lobbying organization and in 1974, the educational and charitable Human Life Foundation; the first issue of the Human life Review was printed in January 1975. He dedicated himself to anti-abortion efforts until the end of his life, eventually retiring from NR to devote himself full time. In 1993, J.P. underwent surgery for throat cancer. He lost his ability to swallow, and to speak. For the next five years he endured further surgeries, radiation, and more cancers, but he never stopped working. On October 16th, 1998, we got the latest issue of the Human Life Review to the printer, he and my mother left the office; he died at 4 am the following morning.

My mother, Faith Abbott McFadden, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, grew up as a member of the Moral Re-Armament (MRA) movement. She moved to New York on her own and, she would say, “read her way” into the Catholic Church (before she met my father), influenced especially by Thomas Merton’s spiritual autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. You can read about her journey in her book, Acts of Faith (Ignatius Press, 1994). She and my father married in 1959 and became the parents of five children. The eldest, Robert Arthur, died in 1994 at age 34, after a 14-month battle with cancer. He had been working as director of the Ad Hoc Committee’s offices in Washington, D.C. Faith wrote many articles for the Human Life Review, including the moving “Ghosts on the Great Lawn” (1986). After J.P.’s death, she joined the staff of the HLR as Senior Editor; she remained its guiding light until her own death from cancer, in August 2011.

My mother, Faith Abbott McFadden, the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, grew up as a member of the Moral Re-Armament (MRA) movement. She moved to New York on her own and, she would say, “read her way” into the Catholic Church (before she met my father), influenced especially by Thomas Merton’s spiritual autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. You can read about her journey in her book, Acts of Faith (Ignatius Press, 1994). She and my father married in 1959 and became the parents of five children. The eldest, Robert Arthur, died in 1994 at age 34, after a 14-month battle with cancer. He had been working as director of the Ad Hoc Committee’s offices in Washington, D.C. Faith wrote many articles for the Human Life Review, including the moving “Ghosts on the Great Lawn” (1986). After J.P.’s death, she joined the staff of the HLR as Senior Editor; she remained its guiding light until her own death from cancer, in August 2011.

Harold O. J. Brown (1933-2007) was a theologian and prominent writer who mobilized the evangelical movement against abortion. He joined the Human Life Review as the Associate Editor in its second issue, Spring 1975, where he also contributed the article “What the Supreme Court Didn’t Know,” a masterful essay about the bad scholarship of Roe v. Wade. The Court, he wrote, flagrantly threw over Judaeo-Christian tradition and the Hippocratic Oath, which condemned abortion, in favor of “pre-Christian paganism,” but that was “puzzling in the light of the fact that sources are readily available, often in English translation, to show that even in pagan antiquity, abortion, although widely practiced, was by no means universally approved, and was indeed explicitly condemned as immoral, dangerous, and harmful to the general welfare, by the most important pre-Mosaic law codes and by some of the most celebrated thinkers, philosophers, and moralists of pagan Greece and Rome.” In the fall of 1976, he left the editorial position to take up teaching duties at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School but remained a contributor and dear friend. His essay, “Euthanasia: Lessons from Nazism,” from our 1987 issue, is reprinted in our book The Reach of Roe (2013).

Harold O. J. Brown (1933-2007) was a theologian and prominent writer who mobilized the evangelical movement against abortion. He joined the Human Life Review as the Associate Editor in its second issue, Spring 1975, where he also contributed the article “What the Supreme Court Didn’t Know,” a masterful essay about the bad scholarship of Roe v. Wade. The Court, he wrote, flagrantly threw over Judaeo-Christian tradition and the Hippocratic Oath, which condemned abortion, in favor of “pre-Christian paganism,” but that was “puzzling in the light of the fact that sources are readily available, often in English translation, to show that even in pagan antiquity, abortion, although widely practiced, was by no means universally approved, and was indeed explicitly condemned as immoral, dangerous, and harmful to the general welfare, by the most important pre-Mosaic law codes and by some of the most celebrated thinkers, philosophers, and moralists of pagan Greece and Rome.” In the fall of 1976, he left the editorial position to take up teaching duties at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School but remained a contributor and dear friend. His essay, “Euthanasia: Lessons from Nazism,” from our 1987 issue, is reprinted in our book The Reach of Roe (2013).

In a collaboration not well-known, J.P. and Brown, along with Dr. C. Everett Koop and Francis Schaeffer and several others, set up the evangelical Christian Action Council in 1975, which had as its purpose awakening the Christian community to the Biblical imperative to defend unborn life. CAC would eventually become Care Net, the marvelous network of pregnancy centers. As Christian journalist Robert Case wrote in his blog, “Case in Point” (“Joe Brown, CAC, and Me,” May 10, 2011): “While the new council drew its distinguished members from the evangelical ranks, it drew its funding from the Ad Hoc Committee in Defense of Life, Inc., a Roman Catholic creation headed by the estimable J.P. McFadden of National Review and run by Washington, D.C. lawyer John Mackey. Without the Roman Catholics there may have been no Care Net organization today!” In 1976 CAC moved out from under the Ad Hoc funding umbrella, but the story remains an early and beautiful one of cooperation in the cause of life.

Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987) was called “America’s First Renaissance Woman” in her obituary in Time magazine. She was a prolific, multi-genre author (fiction, drama, satire, editorial), a politician, and the first American woman to be appointed to an American ambassadorial position abroad. Luce’s influential play, The Women, opened on Broadway in 1936 (and was made a movie in 1939). In 1942, she was elected to Congress, representing the fourth district of Connecticut. In 1944, a tragic accident killed her only child, Ann, and she looked for spiritual guidance, finding it in Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, who instructed her and then received her into the Catholic Church in 1946. Her writing took a more spiritual road after this.

Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987) was called “America’s First Renaissance Woman” in her obituary in Time magazine. She was a prolific, multi-genre author (fiction, drama, satire, editorial), a politician, and the first American woman to be appointed to an American ambassadorial position abroad. Luce’s influential play, The Women, opened on Broadway in 1936 (and was made a movie in 1939). In 1942, she was elected to Congress, representing the fourth district of Connecticut. In 1944, a tragic accident killed her only child, Ann, and she looked for spiritual guidance, finding it in Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, who instructed her and then received her into the Catholic Church in 1946. Her writing took a more spiritual road after this.

She wrote the screen play for Come to the Stable, the 1949 movie about the two nuns who founded Regina Laudis monastery in Connecticut, and edited a collection on saints’ lives (Saints for Now, Sheed & Ward, 1952). Mrs. Luce, a feminist, realized that “induced abortion is against the nature of women.”

As Patrick Allitt wrote in his book, Catholic Intellectuals and Conservative Politics in America, 1950-1985: “In 1978 she withdrew her support for the Equal Rights Amendment (after more than half a century advocating for it) remarking that it was now likely to fail and that a ‘large part of the blame has to fall on those misguided feminists who have tried to make the extraneous issue of unrestricted and federally-funded abortions the centerpiece of the equal rights struggle.’” In Mrs. Luce’s first contribution to the Human Life Review (Winter 1977, “On the Kilpatrick Position”) she wrote: “No one with any intellectual pretensions can ignore the fact that the abortion question (like the slavery question) turns on an either-or biological question that cannot be evaded by an honest mind: Either the child in utero is, from conception, a human life in the process of developing fully into childhood, just as the born infant is a human life in the process of developing fully into adulthood; or the unborn child is a non-human form of life which becomes a human being only by virtue of being born.” Luce was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan in 1983. At her death, J.P. wrote: “Mrs. Luce was indeed our Woman of the Century, justly renowned for having a mind that was . . . well, beautiful, as she was herself.”

Congressman Henry J. Hyde (1924-2007) was affectionately called Generalissimo Hyde by J.P. McFadden. Collaborators in the cause of life from the first days of the Ad Hoc Committee and the Human Life Foundation, Henry Hyde remained one of my father’s best friends and chief sources of inspiration. Hyde, who represented the 6th district of Illinois from 1975 to 2007, was chairman of the House Judiciary and International Relations Committees. He was the first recipient of our Great Defender of Life Award in 2003. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom days before he retired, and President George W. Bush praised him as “a gallant champion of the weak and the forgotten, and a fearless defender of life in all its seasons.” He was the author of the Hyde Amendment, first passed in 1976, which banned the public funding of abortions through Medicaid. (In 1993, Congress added rape and incest exceptions to the life-of-the-mother exception that was there from the start, something, Hyde wrote J.P., that deeply saddened him.) National Review’s obituary noted: “The National Right to Life Committee has estimated, conservatively, that the Hyde amendment has prevented at least one million abortions. That’s one million Americans who are alive today because of Henry Hyde.”

Hyde spoke out forcefully on abortion and was a great leader in the fight against “the unspeakable horror” of partial-birth abortion. His testimony and speeches appeared frequently in the HLR. In a book of his speeches and writings released shortly after his death, Catch the Burning Flag, Hyde wrote: “those who labor for a good cause in the vineyards of politics have reason to keep on keeping on. The classic example of that is William Wilberforce, the English reformer who, more than any other individual, awoke the conscience of his country to end the slave trade in 1807 and to end slavery itself throughout the Empire in 1833. He was told that glorious news only three days before his death, but he must have long known in his heart that it would one day come, whether or not he would live to hear it.”

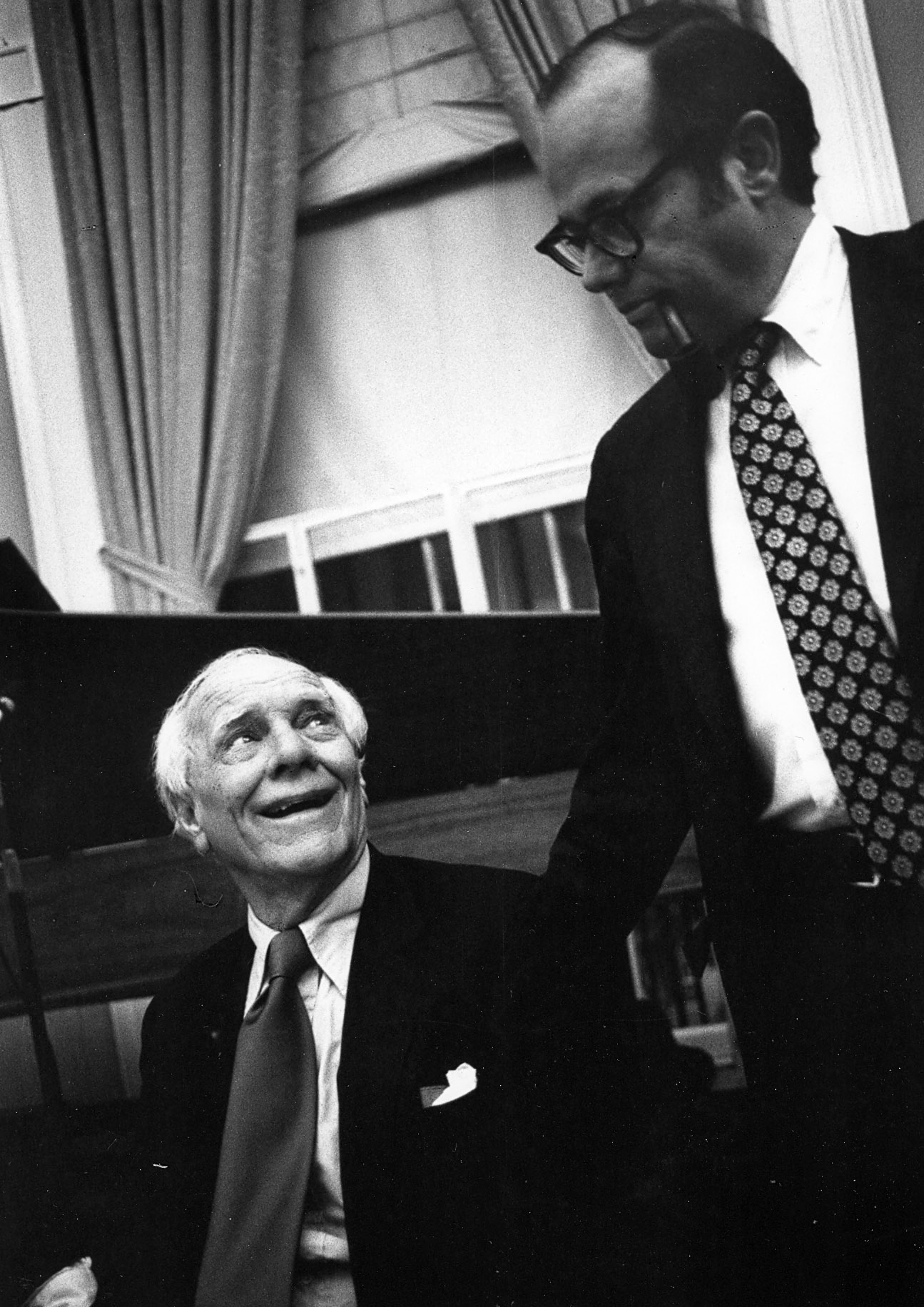

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990) was an English author, satirist (for many years editor of the British humor magazine Punch), TV personality, and in later years, a Christian apologist. He was a soldier and spy during WWII, a socialist turned avid anti-Communist, an agnostic turned Christian. His powerful 1969 book Jesus Rediscovered caused some to call him a Christian mystic.

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990) was an English author, satirist (for many years editor of the British humor magazine Punch), TV personality, and in later years, a Christian apologist. He was a soldier and spy during WWII, a socialist turned avid anti-Communist, an agnostic turned Christian. His powerful 1969 book Jesus Rediscovered caused some to call him a Christian mystic.

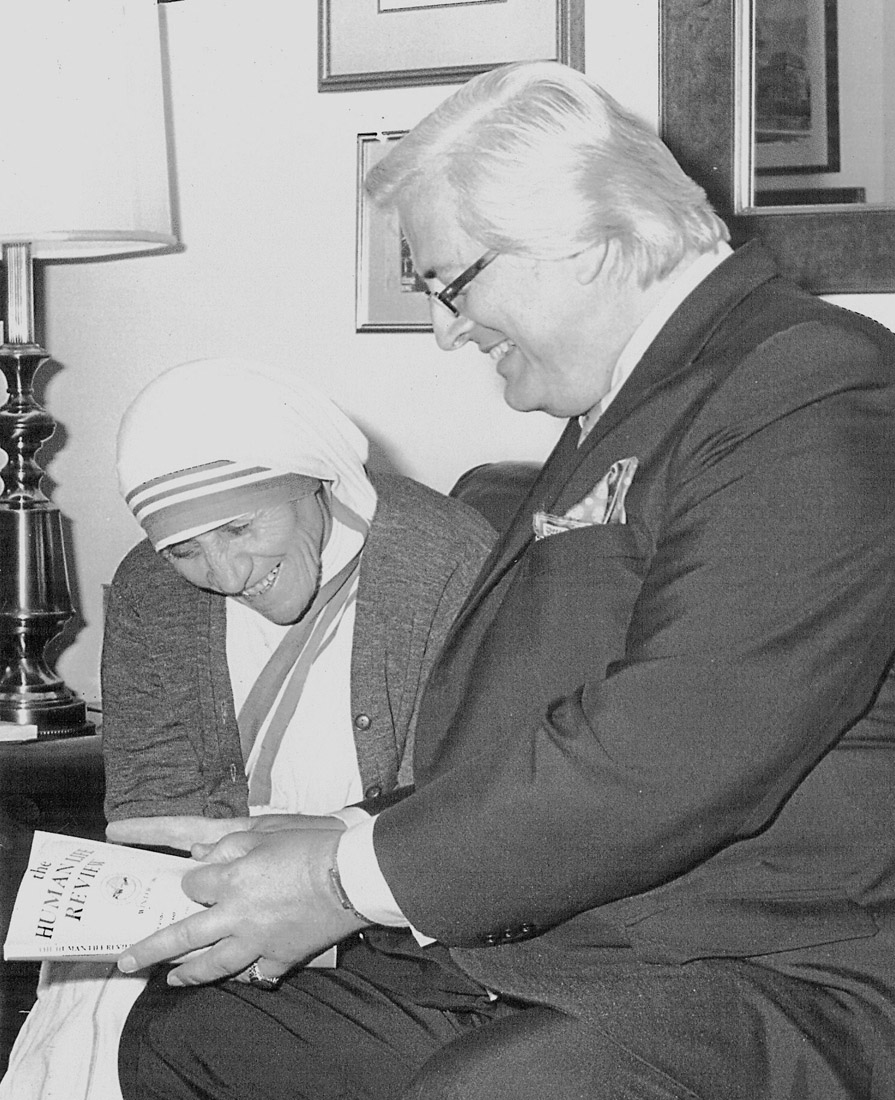

His BBC TV program and book Something Beautiful for God (1971) introduced an unknown nun in Calcutta (Mother Teresa) to the world. J.P., being partial to British literature (his favorite authors included Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and P.G. Wodehouse) was a huge Muggeridge fan, and started writing him in the 60’s—they soon developed a friendly correspondence, and, as J.P. wrote, he was “from the beginning, an intellectual patron” of the Human Life Review. Muggeridge’s first article in the HLR was in the Summer of 1975, a reprint from the London Sunday Times, “What the Abortion Argument is All About.”

At about this time, my parents met Malcolm and his wife Kitty while they were visiting the U.S., and began a lifelong friendship. In 1979, in the same room we are in tonight (the Lincoln Dining Room of the Union League Club), Malcolm Muggeridge, along with Bill Buckley, hosted a testimonial dinner for my father, congratulating him on his launching of the Human Life Review. (I was lucky enough to be the surprise speaker.) On that evening, Muggeridge praised J.P. for being someone whose best cause was a “lost cause” and described him as a man who “combines to a remarkable degree a touch of saintliness with a strong dose of Machiavellianism—one of those mixtures, like gin and bitters, that somehow work together very well.” In 1980, Muggeridge wrote “The Humane Holocaust” for the Review, an essay of haunting beauty and prescience, in which he observed: “. . . the origins of the holocaust lay, not in Nazi terrorism and anti-semitism, but in pre-Nazi Weimar Germany’s acceptance of euthanasia and mercy-killing as humane and estimable. . . . it took no more than three decades to transform a war crime into an act of compassion, thereby enabling the victory in the war against Nazism to adopt the very practices for which the Nazis had been solemnly condemned at Nuremberg.”

Ronald Wilson Reagan (1911-2004) was the 40th President of the United States, and as sitting president, he contributed to the HLR our most famous article so far. In 1983 the Human Life Review published “Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation.” In the introduction to the issue, J.P. wrote: “Mother Teresa, that good woman, rarely if ever speaks without condemning abortion. She once said: ‘Abortion is a crime that kills not only the child but the consciences of all involved.’ The President of the United States too has spoken out often against abortion, and, in our lead article, does so again, also relating it to ‘the conscience of the nation,’ because, Mr. Reagan says, ‘Abortion concerns not only the unborn child, it concerns every one of us.’”

Ronald Wilson Reagan (1911-2004) was the 40th President of the United States, and as sitting president, he contributed to the HLR our most famous article so far. In 1983 the Human Life Review published “Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation.” In the introduction to the issue, J.P. wrote: “Mother Teresa, that good woman, rarely if ever speaks without condemning abortion. She once said: ‘Abortion is a crime that kills not only the child but the consciences of all involved.’ The President of the United States too has spoken out often against abortion, and, in our lead article, does so again, also relating it to ‘the conscience of the nation,’ because, Mr. Reagan says, ‘Abortion concerns not only the unborn child, it concerns every one of us.’”

Mr. Reagan also wrote in his article: “We cannot diminish the value of one category of human life—the unborn—without diminishing the value of all human life.” He concluded: “Abraham Lincoln recognized that we could not survive as a free land when some men could decide that others were not fit to be free and therefore should be slaves. Likewise, we cannot survive as a free nation when some men decide that others are not fit to live and should be abandoned to abortion or infanticide.”

In 1984, Thomas Nelson publishers produced Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation in book form. It included Afterwords by C. Everett Koop, M.D. (“The Slide to Auschwitz”) and Malcolm Muggeridge’s “The Humane Holocaust.” President Reagan remained dedicated to the cause of life. The recently deceased Judge William P. Clark, National Security Advisor under Reagan, wrote in a New York Times Op Ed in 2004 (“For Reagan, all life was sacred”) that “one of the things he (Reagan) regretted most at the completion of his presidency in 1989 . . . was that politics and circumstances had prevented him from making more progress in restoring protection for unborn human life.” And yet, even in his famous “Evil Empire” speech in 1983, Reagan said “Unless and until it can be proven that the unborn child is not a living entity, then its right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness must be protected.”

Maria McFadden Maffucci