GREAT DEFENDER OF LIFE DINNER 2021

OCTOBER 7, 2021

HONORING

MARGARET COLIN AND MARVIN OLASKY

__________________________________________________

Marvin Olasky:

Thank you, David. I will treasure being called a Great Defender of Life, even though the great is an exaggeration. Back in 1990 I profiled two great defenders who had recently written articles in Human Life Review—Henry Hyde and Nat Hentoff. They were men of character but they were also characters, unique individuals.

Henry Hyde was a devout Catholic. His inner office in Washington was very neat and tidy. It included one portrait of Thomas More, two busts of Abraham Lincoln, but three statuettes of Don Quixote. He knew that keeping the Hyde Amendment would always be a battle. He was ready to joust.

The office of Nat Hentoff two miles south of here was extremely untidy. He reviewed jazz albums when they were on vinyl, and threw many on the floor. You had to walk carefully to avoid going crunch, crunch. He was an atheist but he could not accept killing babies.

It takes all kinds of people to make a movement. The pro-life movement is filled with reputable people. But sometimes, in God’s mysterious providence, unborn children benefit from disreputable people. That’s the story I want to tell you tonight. It’s the first time I am telling it publicly.

Until three weeks ago I thought I’d give you the talk I’ve given at many pro-life gatherings over the years. It’s an OK stump speech. But we’re only several blocks from Broadway. You deserve more than a road show.

So, this is the world premiere of some research in progress. It’s not a smooth presentation but you will be the first people to learn the truth about someone I turned into a Great Defender of Life. You will learn that the results were great, even if he wasn’t.

The story is also worth telling because this month is the sesquicentennial—the 150th anniversary—of the conviction of an abortionist who was the villain in the drama.

Here’s some backstory. In 1986 I was an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin. My wife had founded the Austin Crisis Pregnancy Center two years before. We had just had a young woman going through a crisis pregnancy live with us for nine months. That story had a happy ending. So I wanted to write about abortion. I also had to publish a bunch of journal articles to get tenure.

The solution: I wrote academic journal articles about newspaper coverage of abortion over the years. In doing so I could praise pro-life people. I don’t know if that would be possible now, but it worked. One person I brought to life was a reporter named Augustus St. Clair. I didn’t realize then that it was only his name sometimes. His day job put some abortionists in jail. I didn’t realize then that his night work could have caused some abortions.

In 1871 he wrote a great series of articles about abortion called “The Evil of the Age.” If you look him up on the internet, you’ll find articles that are probably there because of my research: He had largely been forgotten. I made him a two-dimensional hero—but while researching the new history of abortion that I’m writing, I have seen the third dimension.

Here’s what I now understand to be the real story, in brief. William Augustus Doolittle Jr., later known as Augustus St. Clair, is born in New York in 1839. At age 19 he marries a beautiful woman, Mary Byington, also 19.

At age 20 William Augustus becomes the rector of an Episcopal church in Yonkers. Too much too soon. He fights with the congregation. The vestry demands that the bishop remove him. The bishop complies. Doolittle is bitter and becomes a Congregational minister. He and his wife have three daughters by the time they’re 26, in 1865.

Then in 1867 he’s gone 150 miles north and is pastor for a half-year at First Baptist Church in Hoosic Falls, near the Vermont border. He doesn’t last long because he becomes sexually involved with the wife of a deacon. He eventually confesses.

William Augustus Doolittle legally changes his name to Augustus St. Clair. He becomes a newspaper reporter in Troy and then Newburgh, N.Y. in 1870 and 1871. According to court documents, he becomes sexually involved with a Mrs. Jenny Erkenbrach. The New York Sun reports she is “a woman of unusual personal attractions.”

Let’s review. Fired from at least two pastoral jobs. Caught in at least two adulteries. But he’s picked up some journalistic experience. The summer of 1871 is extraordinarily busy at the New York Times. On July 12 Northern Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics clash on Eighth Avenue. Members of the National Guard start shooting. Three Guardsmen plus more than 60 civilians, mostly Irish laborers, die.

So, at least 63 deaths. Meanwhile, the Times is in a big battle with Boss Tweed, the corrupt Tammany Hall master manipulator. Times editor Louis Jennings is looking for another way to poke at corruption. His regular reporters are busy. But look—here’s Augustus St. Clair hungry for work. Sure, let him spend a couple of weeks visiting abortionists. See what he can produce. That is Augustus St. Clair’s one shining moment. Here’s the headline and subhead of his story, published on August 23, 1871: “THE EVIL OF THE AGE. Slaughter of the Innocents,. . . Scenes Described by Eyewitnesses.” That last emphasis on eyewitnesses is important. St. Clair is not just spouting off, opining. He visited abortionists and reported what they said. He includes vivid specific detail: “Human flesh, supposed to have been the remains of infants, found in barrels of lime and acids, undergoing decomposition.”

The story would have been better had he included some human interest about what one of the women coming for an abortion looked like. Say someone—I’ll quote here—“about twenty years of age, of slender build, having blue eyes, and a clear, alabaster complexion,” plus “long blonde curls, tinted with gold.” Reporters from the 1830s on had used the looks of abortion seekers and adult victims as a way to generate reader involvement. The looks of that particular woman are relevant because three days after the publication of St. Clair’s big story, a baggage handler at the train station smells a horrible odor emanating from a trunk to be shipped to Chicago. He opens it and finds the corpse of that 20-year-old. The autopsy shows an abortion killed her.

The “trunk murder” receives coverage throughout the United States. Four days later St. Clair writes a follow-up story in the Times. Early in this story, not the first, he provides the description of the young woman that I read to you. Near the end of this story, he says he had happened to see her twice in the office of the abortionist who killed her. He finishes with a flourish, in italics: “I positively identify the features of the dead woman as those of the blonde beauty, and will testify to the fact, if called to do so, before a legal tribunal.” Well. Thirty-five years ago, I thought St. Clair seeing that particular woman was an unlikely coincidence, but in reporting, coincidences do happen. I tried to find out more about St. Clair but came up dry. You all know that the Times is now strongly pro-abortion, so its pro-life role 150 years ago was a good story. I went with it.

Last month, using the resources now available through the Internet, I took another shot at learning more about St. Clair. Something happens soon after St. Clair’s scoop that discredits him among New York journalists. The Brooklyn Eagle calls him “eccentric” and a “much-pulverized reporter.” St. Clair defends a corrupt government official in a way that leads some journalists to conclude St. Clair is corrupt himself.

That may have been a political dispute, but in October, 1872, St. Clair demolishes any remaining belief in his honesty when he testifies during a sensational murder trial. Famed businessmen Jim Fisk and Edward Stokes quarreled over a girlfriend, Josie Mansfield. Stokes shoots and kills Fisk outside a hotel about two miles south of here. After a mistrial, St. Clair, in a subsequent trial, shows up to testify that he saw a pistol in Fisk’s hand, so Stokes purportedly fired in self-defense.

Others did not see a pistol. The Boston Globe declares, “Those who claim to know the witness [St. Clair] say that he is not a man worthy of belief. . . . He would not hesitate to swear to more than he knew, for a consideration.” The Charleston Daily News says, “St. Clair’s story bears the strongest evidence of having been manufactured.”

The Vermont Gazette reports that four men from Hoosic Falls, where St. Clair had ministered—particularly to the deacon’s wife—were ready to swear “that they would not believe St. Clair under oath.” The Chicago Tribune, the Nashville Union, and others all say St. Clair is a liar.

St. Clair in 1874 snags a public relations job for the Liquor Dealers Protective Union of Brooklyn. He arranges travel and hotel reservations for booze dealers arriving at a state convention. In 1875 he is a toastmaster at a Long Island hotel. During the rest of the decade he writes advertising booklets for hotels, with words like these: “Visitors will experience complete satisfaction not only in respect to the refreshments they obtain, but in the charges they pay, and the handsome treatment they will invariably receive.”

In the 1880s he sometimes reuses the name Augustus Doolittle. He appears in this article from 1884: “Henry Van Bunckle, a traveling salesman living at Union Hill, N.J., on Sunday found his wife in company with Augustus Doolittle sitting on the piazza of Tallon’s Hotel . . . He gave Doolittle a severe thrashing and then drove away.”

Over the next 15 years St. Clair apparently picks up some short-term editing jobs in Elmira, New York City, and St. Joseph, Missouri. He briefly does some public relations work in 1898. Census reports show him as still married in Mount Vernon, N.Y., but his wife often appears as “head of household.”

When she dies in 1906, her obituary (as Mary C. Doolittle) says, “Four daughters survive her.” It says she “was at one time considered one of the most beautiful women in Westchester County.” It says nothing about a husband. St. Clair was still alive, though: He died in 1915 in Brooklyn and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

The facts of St. Clair’s life make me doubt the truthfulness of the dramatic ending to his second story: “I positively identify the features of the dead woman as those of the blonde beauty, and will testify to the fact, if called to do so, before a legal tribunal.” If he had improbably seen her, that detail would probably have been in his first story.

Here’s another clue: Police arrest the abortionist whose operation led to the young woman’s death. Prosecutors have to prove her presence in the abortionist’s house. They do so, but the case is not a slam dunk. You’d think St. Clair’s testimony would be crucial—if prosecutors think he’d be a credible witness. It seems they do not. He never testifies.

It also seems the New York Times within a few months decides he is not credible. I do not know whether St. Clair’s name change and his adulteries had anything to do with that. I suspect editors, once they have time to ask hard questions, become suspicious. That’s what happened a generation ago when Washington Post editors took a closer look at the stories of Janet Cooke, and New Republic editors looked closer at the stories of Stephen Glass. Coincidences do happen, but when a story seems too good to be true, it usually is.

But, so what? I have about four minutes left to answer a key question: “Who cares what happened 150 years ago?”

First, I do. I got it wrong. Yes, 35 years ago it was hard to read lots of old newspapers without traveling all over, but a journalist should always admit and correct mistakes. One reason I did not ask some hard questions: I assumed a good guy on life issues would be good. Not necessarily so.

I also thought a reporter and an editor who produced pro-life stories would be pro-life. But to the best of my knowledge, St. Clair never wrote anything about abortion before 1871 and never did again. His editor, Louis Jennings, wrote one good pro-life editorial headlined “The Least of These Little Ones”—but I read last month a book about America he wrote just before becoming editor of the Times. In it he says nothing about abortion.

Nevertheless, Jennings and St. Clair had a big pro-life impact. New laws and compassionate programs emerged. A series of prosecutions commenced. Some abortionists went behind bars, although usually for not very long. Others were scared straight. Publishers put out more books about abortion, including one in 1875 by Elizabeth Evans, The Abuse of Maternity. She documented postabortion syndrome.

I suspect the Times published “The Evil of the Age” because Jennings wanted to show one more way in which city officials were corrupt. Abortionists regularly bribed police and prosecutors to leave them alone. Jennings talked with a hungry freelancer, Augustus St. Clair, about getting a story with all the right elements: human interest, crime, corruption, vulnerable women, death.

Such stories are still all around us, but they are no-fly zones at major newspapers. The Chicago Sun-Times ran a dramatic series about abortionists in 1988. To my knowledge no one has done it again during the past 33 years. As the dead push up through the soil, reporters say “Nothing to see here.” In July 1990 one brave journalist, David Shaw of the Los Angeles Times, documented massive press bias in a 4-part series. Little has changed since then, but major newspapers don’t admit it.

In 2013 major media had another chance to take abortion seriously. Jurors, after a lengthy trial, convicted Philadelphia abortionist Kermit Gosnell for murdering just-born babies. The evidence of killing tiny humans with scissors following botched abortions was grisly, but the Media Research Center found that during the 55 days of the trial, ABC ran 70 segments on shocking criminal cases but nothing on Gosnell.

A vibrant story like “The Evil of the Age” shames much of modern journalism: Now, abortion ideology overrules opportunities for dynamic streetlevel reporting. But it also shames our entire crazy culture. The Me Too movement has had some good effects. Men should not inappropriately touch women, let alone go much further. But what about a man who impregnates a woman and then says “get lost,” or tosses on the bed a few crumpled-up bills and an abortionist’s address?

We need those who truly are great defenders of life. We also need ordinary reporters and editors who don’t turn their backs on extraordinary stories, just because they are ideologically inconvenient. And I thank all of you who have not turned your backs on the least of these little ones.

This talk will turn into a chapter in a book on American abortion history scheduled for publication by Crossway Books in January, 2023.

Margaret Colin:

Wow! Thank you so much! What a ridiculously gracious introduction. So, I was thinking a lot this week, these weeks, about what I could talk about. This is a very intellectual group. There are a lot of lawyers and politicians and really smart people here. Bye! [Starts walking off podium, laughter, returns.] But what I can offer is what it’s like to be pro-life and an actor. I come from a family of pro-life people. My mother was pro-life. I really, truly don’t believe she knew what abortion was till Roe v. Wade, and that made her very political. So she joined Saint Christopher’s, where there was this renegade priest, Fr. Lisante—who is right here [gestures to her table]. Yes! They helped to form a very viable, politically active, community-oriented pro-life group. From there they went on to work all over Long Island, and I believe that they were also part of creating the New York State Right to Life Party, which was for several years the third-largest party in New York State, and I’m very proud of that.

I would like to thank everybody who gave me this award—especially Maria, and of course, Carol Crossed and Feminists Choosing Life of New York, with whom I have worked, and Feminists for Life with Serrin Foster, for whom I have worked. And I would like to thank Fr. Lisante for having me several times on Personally Speaking,* because that is the way that I, as an actress, am able to convey my message.

So when I go to work, people meet me as an actor . . . because I got the job. And then we go to work. And then we figure out what our job is and how to work and as we go along, they discover that I’m pro-life because we hang out. And so now, I’m not one of “them,” I’m one of “us,” and we can dialogue. And I am a very firm believer in dialogue. Sometimes dialogue is almost impossible, so then I try to meet them with love. People I can’t agree with, I try to meet with love. And find an area where pro-choice (ugh) and pro-life can meet together in supporting women who make the choice to keep their babies, and give them the resources they need so that they don’t have to choose abortion.

I’ve been acting since I was nineteen. I’ve worked in television and film, on-stage on Broadway, off-Broadway, in China, in London, in LA, in— where else, who knows? But I’m really grateful. I’ve been in blockbuster films like Independence Day. So I love it when you all come up to me and say: “Oh, you’ve worked with Tom Selleck!” Yes, three times! Three Men and a Baby, on his show [Magnum P.I.] and in—with the gun in my crotch— his latest, Blue Bloods. So yes, I am really blessed to work a lot—soon to be released, Road to Galena—independent films, blockbusters, soap operas, commercials and one musical (that will do it) a few years ago, Carousel.

I cannot say that I have lost work because I was pro-life. I cannot say that. I can say that people were horrified at rehearsal when I was called to come to the White House when President Bush was advocating for making stem cell research more humane. I was invited there with Patty Heaton. And we went, and I was proud to go. But they were shocked in my rehearsal hall at the Manhattan Theater Club that I was pro-life, and one actress literally backed away from me. Which was kind of hard, but I was really glad that I came back and went to work. And they accepted that there was one of them in their midst, and it was “hail-fellow-well-met”—that’s what I experienced. Also, I went to work on Veep. I’ve won an award in the supporting actor category from the Screen Actors Guild [for Veep]. I like winning awards, and I’m so grateful for this one tonight. I’m really grateful and hope to live up to being a Great Defender of Life. I’m going to spend the rest of my life trying to live up to it.

So I worked on Veep, and I played—do you know the show? Do you watch the show? They’re not good, not nice people. But they’re well-drawn characters. They’re really funny, and they reflect on our political condition. So because of my social media, they know I’m pro-life. The show’s liberal and democratic, and I am pulling for my Democrats for Life friends. But these are not they. So, when I went to work for them, it was, again, hail-fellowwell-met. Here’s the material, let’s get to work. You are one of us. Let’s go. Your opinions are welcome. In my experience, there has been no prejudice because I’m pro-life.

The opening episode of a season of Veep that I had a regular role in was broadcast at Lincoln Center. And one of the women characters had an abortion. The callous way that the father of her child referred to the abortion, the callous way it was carried out, the desperateness of the woman character having this experience—it was devastating. There was silence at the end of the episode. Silence. That’s how they premiered the episode.

So in my mind—and I want to hear what you think of this afterwards—that was a very successful show. Because it was horrible. It was agonizing. And I talked to them afterwards, and everybody knew how I felt being pro-life, and so that’s what I want to offer to you. Because a lot of people ask how I was being treated as an actress in the business, and I’m saying, that’s how I am treated. This was a very effective show about the horrors of abortion.

I wouldn’t be up here if it weren’t for my mother [she pauses, momentarily overcome with emotion]. I guess none of us would be here if it weren’t for our mothers.

I base my arguments when I talk to my friends at work on the arguments clearly laid out by Serrin Foster in her much-published speech [“The Feminist Case Against Abortion,”] in this book [holding it up], Women’s Rights. Don’t laugh. There are women’s rights. It’s not an oxymoron. This is an old joke in my family. I have sons, only sons.

I argue the rights of women as the early American feminists did. That they have always considered abortion an abomination, infanticide. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony—Carol sing along with me! [addressing Carol Crossed from the podium]. All of them, all said it was an abomination against women and children. Our movement has been co-opted, since the ’60s, by people who put abortion first. You don’t agree with them. I don’t agree with them. It’s ridiculous.

And that is how I meet my friends at work—with that argument. I don’t offer that I’m Catholic, because people like to dismiss it: “Oh, you’re religious.” Just like trying to get you into bed: “Oh, you’re religious.” But that was then. So my mother was pro-life, my father was a police officer. They brought us to the marches. They turned our recreational vehicle into a pro-life wagon that went all over Long Island. Yes, she interrupted our weekends and tried to save lives all over Long Island. She did. She put up posters and handed out literature and offered the support that women in crisis, young girls in crisis pregnancies need. So that’s how I became a part of it. [Applause]

I have learned so much from my pro-life friends. I continue to learn from them. I’m not as intellectual as this group clearly is. I’m passionate about defending life, and I’m grateful to be in your company and really grateful for the support.

I thank my husband Justin Deas and my son Joseph Deas and my other son Samuel Deas for putting up with me and listening to all this everywhere we go.

And thank you.

*Personally Speaking is a podcast hosted by Msgr. James Lisante (Enlighten Productions, LLC).

George Marlin: Remembering Michael Uhlmann

Thank you, Jack, for your kind words. I should point out that Teddy Roosevelt, Bill Buckley, and I have one thing in common. We all ran for mayor in New York, and we all came in 3rd place. So I’ve had good company. But tonight I am particularly pleased to pay tribute to a man I had the privilege of calling a friend for 45 years, and most recently had the sad duty of being executor of his estate; and that is Mike Uhlmann, who was one of the founding editors and board members of the Human Life Review. Representing his family tonight is his niece Aurelie Uhlmann Cunningham and her husband, the man who gets our blood pressure cooking every morning, Mark Cunningham, the editorial page editor of the New York Post. So, thanks for being here this evening.

Some thoughts about Mike Uhlmann. He was a Catholic kid who grew up in Washington. His father worked for the government down in DC. He was a scholarship kid at The Hill School, Yale University, the University of Virginia Law School. When he was at Yale, he was present at the creation of the modern conservative movement—at Bill Buckley’s place in 1960, where he co-authored with M. Stanton Evans the “Sharon Statement,” which was the founding document of Young Americans for Freedom and a list of principles of the modern conservative movement.

When Mike was at the University of Virginia Law school, he went to a conference, I think it was in Chicago, and met probably one of the great political philosophers of the 20th century, Harry Jaffa, who is noted for his writings on Abraham Lincoln, but is most remembered as the man who wrote Barry Goldwater’s acceptance speech given at the 1964 Republican Convention. So impressed by Jaffa, so taken by him, Mike, after finishing law school, went out to Claremont Graduate School of Political Science, where he studied not only under Jaffa but under that other great political philosopher Leo Strauss. Mike earned his PhD in political philosophy there.

From there he went back to Washington and became the chief counsel to the Senate minority. And back in 1969, when the House of Representatives actually voted to eliminate the Electoral College, Mike wrote the minority report defending the Electoral College; and, to get an understanding of it, shortly after Mike died, in the Winter 2020 edition of National Affairs, a quarterly scholarly journal, Chris DeMuth wrote a piece titled “The Man Who Saved the Electoral College.” And, when it was coming up for a vote in the Senate, several liberal senators—most notably, Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, who as you remember, forced LBJ out of the 1968 presidential race—he called Mike in and said, I read your treatise and you’re right, and

I’m going to vote to keep the Electoral College. And that’s how it was saved. And, hopefully, you can find that paper on the internet and it should be read and handed out to all quarters as they are trying to take it down again.

From there, in 1971, he became counsel to the sainted junior senator of New York, James L. Buckley. And after Roe v. Wade came down, it was Mike who drafted the Human Life Amendment that Jim Buckley introduced into the U.S. Senate. Several years later, in ’74, he led the transition team for President Ford and for the Justice Department, where he was the Assistant Attorney General for Legislative Affairs. He became very tight with another Assistant Attorney General, whose name was Scalia.

In 1980, President Ronald Reagan appointed Mike Special Assistant to the President, Executive Secretary to the Cabinet for Legislative Policy, and Director, White House Office of Policy Development. In the White House, Mike was the keeper of the flame of the pro-life movement. And when I was cleaning out his house out in California, I came across this great loose-leaf binder, which had all of Mike’s memos on the subject of abortion that went through the White House. He also discovered a guy who was his deputy and later pushed him for Attorney General of the United States—that was Bill Barr, who I have had the privilege to call a friend for many years.

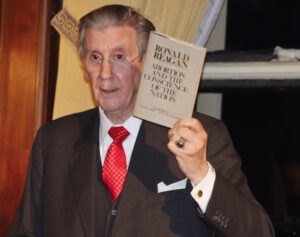

One of the things you should note: You may recall that the Human Life Review, when Reagan was in office, published an essay that he wrote. Mike Uhlmann worked with him on that piece, titled “Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation,” which was later published in this book. [He holds up a copy of Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation, published in 1984.] And I think this was the first book published by a sitting president since Woodrow Wilson that wasn’t just a collection of the usual speeches and stuff. And it was Mike who assisted the president in putting that piece together.

One of the things you should note: You may recall that the Human Life Review, when Reagan was in office, published an essay that he wrote. Mike Uhlmann worked with him on that piece, titled “Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation,” which was later published in this book. [He holds up a copy of Abortion and the Conscience of the Nation, published in 1984.] And I think this was the first book published by a sitting president since Woodrow Wilson that wasn’t just a collection of the usual speeches and stuff. And it was Mike who assisted the president in putting that piece together.

In 1989 when President George H. W. Bush took office, Mike got a call from Boyden Gray, who was then-White House counsel to the president. He told Mike Bush would be nominating his first court appointment—it was the Washington DC circuit. He said the president wanted to put his first best step forward and nominate him to that post. Mike at the time had five kids for whom he needed money to educate, so he was hesitant about taking it. But he told me that he was walking through the Capitol and a guy who was Chairman of the Judiciary Committee—I think his name is Joe Biden—you may have heard of him— came up to him and said, “Hey, Mike, I hear the President is going to be sending down your name. I can’t wait to subpoena all your memos from the Reagan White House.”

And so Mike turned down the nomination because he was afraid he was going to get “Borked,” and he didn’t want to embarrass President Bush. But he recommended in his stead a guy by the name of Clarence Thomas. And if you read Clarence Thomas’s memoirs—I met him at a dinner several years ago in Philadelphia. I’ve been Chairman of the Board of the Philadelphia Trust Company for the past 23 years, and Mike was on my board for 20 years. So, I went up to Clarence Thomas and I said, you know, I’m a good buddy of Mike Uhlmann. And he looked at me and said, if it were not for Mike Uhlmann, he would not be on the U.S. Supreme Court. So, Mike turned it down and gave it to Clarence Thomas, which I don’t think is a bad day’s work.

Afterwards, Mike was the senior vice president of the Bradley Foundation. And then, from 2003 until his death in 2019, he was professor of Government at the Claremont Graduate School of Political Science. Mike trained a generation of young conservatives who are now working in government, teaching in universities—and we have one in Washington by the name of Senator Tom Cotton. There’s some talk of him running for president of the United States.

So, when we look back on his life: He was a founder of the Human Life Review—he and Jim McFadden were great comrades. And with his behind-the-scenes work in Washington, Mike was truly one of the unsung heroes of the conservative movement.

And you have a copy [in guests’ gift bags] of my new book called Mario Cuomo—The Myth and the Man, which I was delighted to dedicate to Mike. Mike went over the two chapters on Mario as a public intellectual, which is sort of an oxymoronic term but . . . I was very pleased he finished that shortly before he died. However, to remember Mike, I have this on the dedication page: If you google his name under “Uhlmann’s Razor,” you will see pictures of Mike come up with this statement: “When stupidity is a sufficient explanation, there is no need to have recourse to any other.”

Mike Uhlmann, an unsung hero of the conservative movement, may his soul and all the souls of the faithfully departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

Thank you very much.