Ignoring Surgical Abortion’s Effect on Infant Mortality in Ohio

A popular indicator of a nation’s health is the rate of infant mortality (the death of an infant within the first year of life). Logic would seem to dictate that technologically and medically advanced countries like the United States would have low rates of infant mortality compared to other similarly advanced countries, but this is not the case. The U.S. infant mortality rate (5.8 deaths under one year of age per 1000 live births) is 71 percent higher than the comparable country average (3.4 deaths).1

Over the last decade, the infant mortality rate in the United States has prompted great concern and debate. A majority of research on this subject seems to indicate that, after accounting for reporting differences among countries, the mortality disadvantage in the U.S. is driven by poor birth outcomes among lower socioeconomic status individuals, who are aggressively targeted by abortion marketing in this country. A 2016 American Economic Journal article indicates that this accounts for 30 to 65 percent of the difference.2

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the state of Ohio has had the dubious distinction of being among those states with the highest rate of infant mortality in the nation.3 When broken down by race/ethnicity, the infant mortality rate among black women is disproportionately higher. According to a 2017 comparison among the 50 states and the District of Columbia, the nationwide rate of infant mortality that year among non-Hispanic black women was 10.9, and the infant mortality rate among non-Hispanic black women in Ohio was a dismal 14.5, second highest in the nation.4 A majority of studies find that the number one cause of infant mortality is premature birth, closely followed by low birth weight. Clearly one means of reducing infant mortality, then, would be to reduce the incidence of premature births. To do that, we need to explore possible reasons why they are currently so high. One of these reasons that stands out over the course of many studies conducted in a variety of places over many years is prior abortion.

For those unaware of how abortion could affect a future pregnancy, you must understand that in a pregnant woman, the cervix is integral to the maintenance of the pregnancy by forming an impenetrable barrier against microorganisms that might otherwise travel from the vagina into the uterus and threaten the developing human being. Weakness of the cervix can cause this barrier to be defective, and is associated with subsequent preterm births. During a surgical abortion, the cervix is forced open to remove the child. Forced dilation of the cervix may damage and weaken it, thus increasing the risks of infection, premature birth, or a late-term miscarriage in subsequent pregnancies.

Concerned about the racial disparities in birth outcomes, in 2012, the Ohio Department of Health and local partners collaborated to create the Ohio Equity Institute to address these disparities in the nine Ohio counties where they were greatest. Since then, there have been many meetings to discuss the problem and to develop an action plan.

In 2016, a summit meeting sponsored by Ohio Equity Institute members was held in Akron to discuss the impact of racism on infant mortality, noting that some of the highest rates of infant mortality in Ohio were located in two zip codes in Akron with predominantly black populations. Shortly thereafter, a program called “Full Term First Birthday Akron” was developed with the mission of educating and informing citizens of programs available in the community that promote healthy, full-term pregnancies. The priority concerns of the program are: 1) to address structural racism (with the help of health and social services, education and workforce development, financial empowerment initiatives, and housing initiatives); 2) to reduce prematurity (by promoting healthy pregnancies through prenatal care, fatherhood involvement, progesterone therapy, and birth spacing); and 3) to eliminate sleep-related deaths. These priority areas are used to identify those at risk for an infant mortality event.

At that very first summit meeting, Right to Life of Northeast Ohio (RTLNEO) requested to be part of the collaborative effort to combat infant mortality but were ignored. This was in spite of the fact that RTLNEO provided a packet of medical information that pointed to a link between surgical abortion and preterm birth in subsequent pregnancies. This was no mere exercise in antiabortion activism, but an effort to help identify women who might be among those most at risk of giving birth prematurely, to foster early intervention to help prevent preterm birth in post-abortive pregnancies. Sadly, RTLNEO was informed that abortion was not a variable that the group would consider in its quest to reduce infant mortality. A further request to be notified of subsequent meetings was also ignored. However, RTLNEO was notified by an inside source, and was able to attend many of the meetings. Ironically, the local Planned Parenthood, which does not provide prenatal care, was accepted as a formal group collaborator.

At the 2019 Akron Health Equity Summit meeting, RTLNEO submitted a statement for the Q & A session which pointed out that Akron’s Summit County had a black population of 15 percent but accounted for 50 percent of its abortions. In addition, RTLNEO noted that the zip codes with the highest rates of black infant mortality also had significantly higher abortion rates. Why, then, was prior abortion history not being considered as a relevant variable in the quest to reduce future infant mortality incidents? The physician answering the questions replied “abortion is a safe medical procedure that has no bearing on infant mortality” and quickly moved on. Yet the same meeting saw speakers who suggested we should measure cortisol levels in women’s hair to monitor the effect of stress on infant mortality, and also a speaker from Planned Parenthood who maintained that the key to preventing infant mortality was to teach responsible sex education in the schools.

In July of 2020, RTLNEO sent all of the information and documentation in this article to many local and state health department officials and members of the infant mortality prevention group asking for feedback, and again requested to be part of the group collaborative effort to combat infant mortality. To date, there has been no response, suggesting an incomplete commitment on the part of the Ohio Equity Institute to “following the science.”

A Brief Overview of Worldwide Studies Regarding Induced Abortion’s Effect on Future Pregnancies

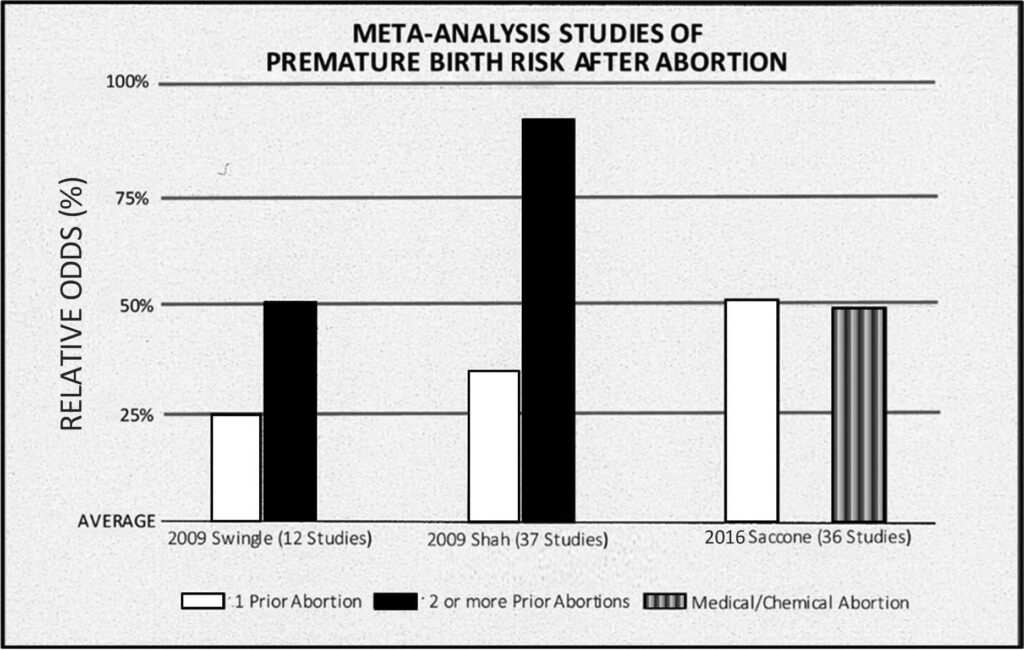

There are over 140 studies in the medical literature (at least 18 done in the United States) that find induced abortion increases the risk of prematurity and/or low birthweight in subsequent pregnancies, thus posing risks for future, wanted children. Many of the earlier studies were reviewed by Calhoun et al.5 A 2009 compilation of 12 studies from around the world found that the odds of experiencing a preterm birth (less than 37 weeks) increased by 25 percent after one abortion all the way to 51 percent following two or more abortions.6 Another report (2009) of 37 international studies, carefully chosen for their scientific rigor, concluded that after a woman had a first or second trimester abortion, this increased the odds of a future preterm birth by 36 percent; after two or more abortions, the odds of preterm birth increased by 93 percent. The study also found the odds of delivering low birthweight (less than 5.5 pounds) infants increased by 35 percent after one abortion and by 72 percent after two or more abortions.7 A more recent (2016) meta-analysis analyzed data from 36 studies, 28 of which involved 193,297 women who had surgical abortions.8 Compared to controls, women with a prior surgical abortion faced a 52 percent increase in the odds of having a subsequent preterm birth; they also faced a 41 percent increase in the odds of delivering a low birthweight child. Three of the groups studied involved 10,253 women who had a prior medical abortion. Compared to controls, this group faced a 50 percent increase in the odds of having a subsequent preterm birth. The chart below illustrates the increasing risk of premature birth after multiple abortions based on the 2009 and 2016 studies mentioned above.

Chart adapted from the original in the companion booklet to the film Hush: A Liberating Conversation about Abortion and Women’s Health

The most recent (2020) large study involved 418,690 first-time Finnish mothers with singleton births between 1996 and 2013.9 The study population included 364,392 women who had undergone no previous abortion, 46,589 who had undergone an early induced abortion (less than 12 weeks gestation), and 7,709 who had undergone a late induced abortion (12 or more weeks gestation). A regression analysis controlled for maternal age, marital status, smoking status, number of previous abortions, method of previous abortion, and the interval between pregnancies. When comparing groups, the authors found:

1) Women who had early induced abortions compared to those with no abortions were significantly more likely to experience perinatal deaths, low birthweight infants, and infants who were small for their gestational age. Compared to those with no abortions, women who had late induced abortions were significantly more likely to experience perinatal deaths, “extremely” preterm births (less than 28 weeks) or “very” preterm births (before 32 weeks), and births of infants with very low birthweight (under 1,500 grams) or low birthweight (under 2,500 grams).

2) And, as might be expected, women who had late abortions experienced greater adverse outcomes than those having an early induced abortion.

National Data

Prematurity is the leading cause of death among newborn infants. Between 1980 and 2005, the preterm birth rate in the U.S. increased by 43 percent, corresponding to the steady rise in legal induced abortions from 1969 through 1981.10 According to the CDC, babies who died of preterm-related causes accounted for 36 percent of all infant deaths in 2013.11 Moreover, those who survive may face lifelong problems. These include the possibility of mental retardation, cerebral palsy, breathing and respiratory problems, vision and hearing loss, and feeding and digestive problems.12 Prematurity has also been linked to lower levels of education and more childlessness in both women and men followed into adulthood. Women who were preemies were more likely to give birth to preemies themselves.13

There has long been a racial disparity in the number of abortions. In 2016, although blacks made up approximately 13.9 percent of women in their childbearing years, they accounted for 38 percent of the abortions, or 2.7 times the number of abortions one would expect, given their percentage of the population.14 As mentioned earlier, there is also a racial disparity in blackwhite infant mortality rates. In 2016 the black infant mortality rate was 11.4 for every 1,000 live births, or 2.3 times higher than the white rate of 4.9.15 Similarly, black mothers are more likely to experience preterm births, particularly births prior to 34 weeks of completed gestation. In 2016, the black rate of early premature births was 4.93, which was 2.1 times higher than the white rate of 2.33.16

A recent national study of over 2.1 million birth certificates from 20152017 found that even women of high socioeconomic status who were black or mixed black/white race were more likely to experience premature births than were white mothers. Unfortunately, although the study considered nine independent variables, it did not consider abortion as a possible causal factor.17

Ohio Data

As we can see in Tables 1 and 2 below, a nine-year review of black and white Ohio women of child-bearing age tends to mirror the national pattern. That is, black Ohio women have a disproportionate number of abortions, and a corresponding disproportionate rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes. These include a higher rate of overall infant mortality and of neonatal mortality.

|

Table 1. Abortion Disparity and Infant Mortality Disparity for Ohio Black and White Women of Childbearing Age (15-44), 2010-2018 |

||||

|

Year |

% of Black Abortions |

% of Blacks in Population |

Black/White Abortion Disparity Score |

Infant Mortality Disparity Score |

|

2010 |

42.9 |

15.4 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

|

2011 |

42.5 |

15.5 |

2.7 |

2.5 |

|

2012 |

39.5 |

15.4 |

2.6 |

2.2 |

|

2013 |

40.5 |

15.4 |

2.6 |

2.3 |

|

2014 |

44.9 |

15.4 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

|

2015 |

46.8 |

15.4 |

3.0 |

2.7 |

|

2016 |

47.2 |

15.4 |

3.1 |

2.6 |

|

2017 |

47.4 |

15.4 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

|

2018 |

47.9 |

16.8 |

2.8 |

2.6 |

• Percent of black abortions were calculated from Tables 5a in the Ohio Department of Health “Induced Abortions in Ohio” report for each year. Only black and white resident abortions were considered, since the U.S. Census collects its data from residents of each state.

• U.S. Census estimates for percent of Ohio black women (15-44) in the population were collected from its “American FactFinder” website during the week of March 15, 2020.

• Abortion Disparity Score is the percent of black abortions divided by the percent of black females of reproductive age in the population of black and white Ohio women aged 15-44, or the “excess” of black abortions that might be expected, given black women’s percentage of the population.

• Infant Mortality Disparity Score is the black infant mortality rate divided by the white infant mortality rate. Source: Ohio Department of Health, “2018 Infant Mortality Annual Report,” p. 7.

As can be seen in Table 1 above, as abortion disparity scores increase or decrease, infant mortality disparity scores tend to increase or decrease. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between these two variables is positive and strong (r = .86), and the coefficient of determination (R2) equals .74, indicating that 74 percent of the fluctuation in infant mortality disparity scores is accounted for by the fluctuation in abortion disparity scores.

|

Table 2. Abortion Disparity and Neonatal Mortality Disparity for Ohio Black and White Women of Childbearing Age (15-44), 2010-2018 |

||

|

Year |

Black/White Abortion Disparity Score |

Neonatal Mortality Disparity Score |

|

2010 |

2.8 |

5.3 |

|

2011 |

2.7 |

6.8 |

|

2012 |

2.6 |

4.9 |

|

2013 |

2.6 |

5.8 |

|

2014 |

2.9 |

6.6 |

|

2015 |

3.0 |

6.8 |

|

2016 |

3.1 |

6.4 |

|

2017 |

3.1 |

7.7 |

|

2018 |

2.8 |

4.7 |

• See notes 1-3, Table 1

• Neonatal Mortality Disparity Score is the difference between the black neonatal mortality rate and the white neonatal mortality rate in each year. Source: Ohio Department of Health, “2018 Infant Mortality Annual Report,” Figure 5, page 10.

As can be seen in Table 2 above, as abortion disparity scores increase or decrease, infant neonatal disparity scores tend to increase or decrease. Pearson’s correlation coefficient between these two variables is a fairly strong positive correlation (r = .70), and the coefficient of determination (R2) equals .49, indicating that 49 percent of the fluctuation in neonatal mortality disparity scores is accounted for by the fluctuation in abortion disparity scores.

According to Chris Mosby’s article “Black Infants More Likely to Die in Ohio, Report Says,”18 in “2018, prematurity-related conditions remained the leading cause of infant death in Ohio, comprising almost one-third of deaths.” Mosby also notes that “Nine Ohio counties accounted for nearly 66 percent of all infant deaths statewide.” Those counties and their 2018 Black/ White Abortion Disparity Scores were Butler (4.2), Cuyahoga (2.4), Franklin (2.5), Hamilton (2.4), Lucas (2.7), Mahoning (3.3), Montgomery (2.5), Stark (3.6), and Summit (3.3).19 Likewise, six of these counties had high Black/White Infant Mortality Disparity Scores: Cuyahoga (3.4), Franklin (2.3), Hamilton (3.8), Lucas (2.9), Montgomery (1.9), and Summit (4.3).20

The Ohio Commission on Infant Mortality was created in 2014 with the goal of improving Ohio’s infant mortality rate. At the time the commission was created, Ohio ranked 46th in the nation for overall infant mortality and 50th for black infant mortality. This commission spearheaded Senate Bill 332, passed by the Ohio legislature in 2016, and then contracted with the Health Policy Institute of Ohio to collect data and produce a report on how to reduce infant mortality. Prior to the bill’s passing, RTLNEO contacted its sponsors requesting that they amend the language of the bill to require that prior abortion data be collected in infant mortality cases, since there is currently no database that can correlate the two statistics. Collecting data on how many Ohio infants who died in the first year of life were born to mothers who had prior abortions would be extremely valuable in predicting risk factors in future pregnancies of wanted children. However, neither of the bill’s sponsors ever responded to the request, and it passed without the amendments. A 233-page report with policy recommendations regarding the effect of housing, transportation, education, and employment on infant mortality was issued in December 2017. The report contains no mention of the impact of prior abortion on infant mortality.

The subject of abortion can be volatile and highly politicized, but that should not permit us simply to ignore evidence of a relationship between women who have undergone abortion and the health and wellbeing of them and their future children. In this case, there is a well-established relationship between prior abortion and the risk of premature birth or infant mortality. Prior abortion is of course not the only source of risk of infant mortality, and therefore the work that the Ohio Equity Institute and collaborative groups do to address socio-economic factors that can affect birth outcomes is highly commendable. However, ignoring the risks associated with prior abortion can threaten the achievement of more positive pregnancy outcomes. Gathering information on the prior abortion history of women in this program can contribute to better outcomes for present and future pregnancies by identifying those at most risk of preterm/low-birthweight events so that progesterone or other medical therapies can be administered at the earliest possible time. It is a tragedy when a mother chooses to end the life of her preborn child through abortion. However, it is an additional tragedy when the risk that prior abortion poses to subsequent pregnancies of wanted children is ignored.

To omit addressing the relationship between prior abortion and adverse outcome in future pregnancies for women in these and all Ohio counties would seem to be the result either of:

• unfamiliarity with the medical literature on this topic,

• racism,

• and/or the acceptance of the ideologies of the population control and pro-choice movements, which publicly deny the findings of science, and do not want to inform women that legal induced abortion is dangerous to their physical and mental health, and to the health of their future, wanted children.21

We cannot afford to be selective in our commitment to “following the science” wherever the facts lead us.

NOTES

1. Rabah Kamal, Julie Hudman, and Daniel McDermott, “What do we know about infant mortality in the U.S. and comparable countries?” Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, October 18, 2019, accessed 6/26/2020, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/infant-mortality-us-compare-countries/

2. Alice Chen, Emily Oster, and Heidi Williams, “Why is Infant Mortality Higher in the United States than in Europe?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2016, 8(2): 89-124 http:// dx.doi.org/10.1257/pol.20140224

3. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/infant_mortality_rates/infant_mortality.htm

4. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/infant-mortality-rate-by-race-ethnicity/

5. Byron C. Calhoun et al., “Preterm Birth and Abortion,” Research Bulletin 20:2 (Fall, 2007). Another review of studies from June 1972 through February 2015 is “Research on Abortion and Preterm Birth,” Prevent Preterm (2010, updated 2017).

6. Swingle HM, et al., “Abortion and the risk of subsequent preterm birth,” Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 2009.

7. P.S. Shah and J. Zao, “Induced Termination of Pregnancy and Low Birthweight and Premature Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (May 19, 2009). Online.

8. Gabriele Saccone, Lisa Perriera, and Vincenzo Berghella, “Prior Uterine Evacuation of Pregnancy as Independent Risk Factor for Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” America Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 214:5 (May 2016):572-591.

9. K.C. Situ, Mika Gissler and Reija Klemetti, “The Duration of Gestation at Previous Induced Abortion and Its Impact on Subsequent Births: A Nationwide Registry-Based Study,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica” (March 3, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13788

10. Brent Rooney, Byron C. Calhoun and Lisa E. Roche, “Does Induced Abortion Account for Racial Disparity in Preterm Births, and Violate the Nuremberg Code?” Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons 13:4 (Winter 2008):102-104. According to the Guttmacher Institute, after an initial peak of 1,577,300 in 1981, abortions fluctuated just under 1.6 million until they reached a final peak of 1,608,600 in 1990, after which they generally declined to 862,320 in 2017.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Premature Birth,” www.govFeatures/ PrematureBirth/ Page last updated November 7, 2016.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC Features: Premature Births,” www.cdc.gov/Features/PrematureBirth/

13. Geeta K. Swamy, et al. “Association of Preterm Birth with Long-Term Survival, Reproduction, and Next-Generation Preterm Birth,” Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 299:12 (2008):1429-1436.

14. Population estimate based on American Fact Finder: Age and Sex, 2016 Population Estimate,

U.S. Census Bureau. Downloaded 3/25/2020. Percent of Black abortions from “Abortion Surveillance, United States, 2016,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Surveillance Summaries (Nov. 29, 2019), pp. 9-10.

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Reproductive Health: Infant Mortality,” p. 3.

16. “Births: Final Data for 2016,” National Vital Statistics Reports, 67:1 (January 31, 2018), p. 8 and Table 13, p. 35.

17. Jasmine D. Johnson, Celeste A. Green, Catherine Vladutiu and Tracy Manuch, “Racial Disparities in Prematurity Persist Among Women of High Socioeconomic Status (SES).” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (February 7, 2020). DOI: https:// doi. org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.060

18. Chris Mosby, “Black Infants More Likely to Die in Ohio, Report Says” (2/26/2020), https://patch.com/ohio/cleveland/black-infants-more-likely-die-ohio-report-says

19. Black/white abortion disparity scores computed from 2018 population estimates of black women in these counties by the U.S. Census Bureau, and black Ohio resident abortions by county in Ohio Department of Health, “Induced Abortions in Ohio, 2018” (September 2019).

20. The Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, did not compute infant mortality rates for Butler, Mahoning, and Stark counties since “rates based on fewer than 10 deaths” in one or more of the years covered “do not meet standards of reliability or precision.” See Figure A1: Trends in Infant Mortality Rate (per 1,000 live births), by OEI County and Race (2014-2018), p. 25, Ohio Department of Health, “2018 Infant Mortality Annual Report.”

21. Raymond J. Adamek, “Legal Abortion Threatens Health and Fertility: Why Aren’t Women Informed?” The Human Life Review, 43:4 (Fall, 2017):27-37.

___________________________

Original Bios:

Denise M. Leipold is the executive director of Right to Life of Northeast Ohio. She works in collaboration with pro-life adult and youth groups and churches throughout northeast Ohio presenting programs, education, advocacy, and more to improve the culture of life, and testifies regularly before local and state legislative committees on life issues. Raymond J. Adamek is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Kent State University, where he has taught courses in family, statistics, and research methods. He has been published in many professional journals and other outlets dealing with life issues. He is also an emeritus board member of Right to Life of Northeast Ohio.