Breaking Free from the Pro-choice Captivity of a Church

In that infamous year 1968, the Evangelical United Brethren Church and the Methodist Church entered into a union to form The United Methodist Church. The new denomination boasted a membership of more than eleven million members, took its place among the “mainline” churches in the United States (sometimes called “the seven sisters” to refer to their WASPish establishment nature), and joined the National Council of Churches (NCC) and the World Council of Churches (WCC).

United Methodist elites—high-steeple pastors, bishops, and professors—presumed they would provide the religious leadership needed by American society and government. To accomplish this, they believed the church needed to be “relevant.” So these elites were forever responding to—usually by seeking the approval of and putting their stamp of approval on—whatever was happening or popular in American culture.

In 2018, United Methodists celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of our denomination. To inform the festivities, the church’s General Commission on Archives and History produced a 10-minute video of the denomination’s history, which was titled “1968 Uniting Conference of The United Methodist Church” and posted it on YouTube. In the video (at 2:20/10:38), a confident, young, future bishop, Rev. A. James Armstrong (1924-2018), boasted of his new church’s serious desire to be culturally relevant: “There are specific issues coming before the conference—race and riots, war and peace, ecumenism. You know, I think apart from these, and beyond them, is the much broader and more important issue of whether the church—both in the local congregation and through its larger official structures—is going to relate to the revolutions that are a part of our own time. I think it is the responsibility of the church to gear itself up to be a part of God’s activity in this world.” Is there any doubt that Rev. Armstrong wanted the new-born United Methodist Church to grow up in a hurry and get behind “the revolutions that are a part of our time?”

(Some held a different vision for The United Methodist Church. For example, Dr. Albert C. Outler, a professor of historical theology at Southern Methodist University, who could be understood to be the father of the denomination. At the Uniting Conference, he preached: “We seek to be a church [that is] truly catholic, truly evangelical, truly reformed . . . semper reformanda, perennial reformation” [7:43/10:38].)

With social activism near the top of its priorities, the new denomination began meeting to hammer out its principles and practices. The 1968 General Conference established “planned parenthood” as a social principle that United Methodists should follow (The Book of Discipline [1968], Paragraph 96.III.A, p. 54). Four years later, the 1972 General Conference took on abortion more directly and approved these sentences: “Our belief in the sanctity of unborn human life makes us reluctant to approve abortion. But we are equally bound to respect the sacredness of the life and well-being of the mother, for whom devastating damage may result from an unacceptable pregnancy. In continuity with past Christian teaching, we recognize tragic conflicts of life with life that may justify abortion. We call all Christians to a searching and prayerful inquiry into the sorts of conditions that may warrant abortion. We support the removal of abortion from the criminal code, placing it instead under laws relating to other procedures of standard medical practice. A decision concerning abortion should be made only after thorough and thoughtful consideration by the parties involved, with medical and pastoral counsel” (The Book of Discipline [1972], Paragraph 72D, pp. 86 and 87.)

In those early General Conferences, the dye was cast, the direction set. The United Methodist Church would be a church that would approve of—or at least understand the need for—abortion. The social-activist wing of the church went so far as to help establish the Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights (RCAR).

Every four years since 1972, General Conference has added pro-life provisions and language to the church’s teaching. Even so, official United Methodist teaching has remained pro-choice. During this time, United Methodist bishops have seemed content with their church’s teaching on abortion. Occasionally, an individual bishop or the Council of Bishops ventured into the political arena to support pro-choice candidates or policies. Otherwise, they were largely silent for over 30 years.

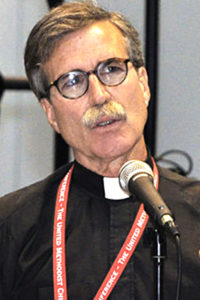

That general silence was broken by Bishop Timothy W. Whitaker of the Florida Area of The United Methodist Church, on January 24, 2005. He spoke from the pulpit of Simpson Memorial Chapel in the United Methodist Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC., the site of countless hours of pro-choice activism over the decades. Looking out a window to his left, the bishop would have seen the United States Supreme Court building across the street. That morning, Bp. Timothy Whitaker became the first United Methodist bishop to preach a sermon consistent with the Gospel of Life. (Titled “Do No Harm,” the sermon can be found and read at lifewatchumc.files.wordpress.com: Click on “Newsletters,” then “Archives,” then “2005,” and finally “March”.)

Bp. Whitaker begins with John Wesley’s General Rules; continues with a discussion of the Biblical promise and task of peace; urges the need to reject violence and do theology, not follow ideology; and admonishes United Methodists to defend human life. He ends his sermon:

I am a bishop, not a philosopher or a politician. I do not profess to understand all the complexities involved in the philosophical debates about when a human being becomes a “person.” Nor do I know the answers to all the questions raised about what should be the law of the land in America. Yet I can feel; and as a United Methodist, often I am better at feeling than thinking. What I feel is revulsion at the moral horror that is abortion. This revulsion is magnified when I reflect upon the fact [that], as Carl Braaten [Lutheran theologian] has said, “ninety-nine percent of all murders in the United States are abortions.” I would like to be a bishop of a church that knows how to make philosophers and politicians feel the same revulsion of the moral horror of abortion.

Perhaps this feeling of revulsion against the horror of abortion is a feeling shared by most human beings. Certainly, Christians have feelings others may not have, because we have been told the Gospel. For Christians, revulsion at the moral horror of abortion is a sensibility shaped by the story of God’s purposes told in the Bible.

It is often said that there is no clear prescription against abortion in the Bible. That is because such a horror is unthinkable and unspeakable to the people of Israel and to the people who are called the Church. The grand story of God’s gift of peace and God’s opposition to the sin of violence compels us to be a people who try to protect the unborn from killing and to work for a culture of life.

From the very beginning, Christians everywhere have felt this revulsion against the killing of human life. As Christians moved into the wider world, where abortion was not unthinkable or unspeakable, they had to apply the divine commandment against murder to the horrible practice of abortion. They did so because of their knowledge of the God of peace in the story of the Bible.

In our time and place, in our own Christian communion, we who are United Methodists also have a responsibility to live according to our first rule, which is to do no harm. Do no harm to the unborn! Do no harm to the witness of the Church as a peaceable people! Do no harm to the Gospel of peace!

Our General Rules are not legalistic prescriptions, but concrete expressions of how we shall actually live in response to the grace of God. The rule to do no harm is not a harsh law; it is a gracious invitation. It is an invitation to live in communion with the God of peace, to whom be glory, honor, and rule forever. Amen.

With these words—with the Word of God!—Bishop Timothy Whitaker shattered an unholy silence in The United Methodist Church. In doing so, he declared that the church’s task is not to catch and ride the cultural currents of the time—which The United Methodist Church had done since its birth in 1968. Rather, the church’s task is to trust, obey, and serve the God of Life and the Gospel of Life. This God and this Gospel stand with the weak, including the unborn child and his or her mother.

Bp. Whitaker’s sermon was a shot heard ‘round The United Methodist Church. His word provided a reforming infusion of the catholic and the evangelical, as Dr. Outler had hoped, into a denomination that had been hell-bent on following the elite currents of American culture.