Exequies and Lamentations: The Waste Land Now

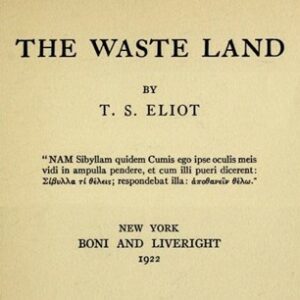

Some years back, some of my readers might remember, an advertisement for corn whisky ran on billboards across the country: “Old Grand-Dad—Over a Hundred Years Old and Still in the Bars Every Night.” Something of the same might be said about T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). Its centennial has come and gone but still we can be struck by passages in the poem that speak to our own age with an uncanny prescience. Of course, we live in an age of accelerated decadence, where much in our culture, our manners, our public life, and what ought to be our moral norms is profoundly disordered; yet over a hundred years ago, Eliot nicely delineated the corruption that now defines us, and most of it issues from our abuse of the procreative gift that God gives his licentious creatures. Here the poet captures the gift’s undoing in the conversation of two cockney women in a public house at closing time.

When Lil’s husband got demobbed, I said—

I didn’t mince my words, I said to her myself,

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Now Albert’s coming back, make yourself a bit smart.

He’ll want to know what you done with that money he gave you

To get yourself some teeth. He did, I was there.

You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.

And no more can’t I, I said, and think of poor Albert,

He’s been in the army four years, he wants a good time,

And if you don’t give it him, there’s others will, I said.

Oh is there, she said. Something o’ that, I said.

Then I’ll know who to thank, she said, and give me a straight look.

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

If you don’t like it you can get on with it, I said.

Others can pick and choose if you can’t.

But if Albert makes off, it won’t be for lack of telling.

You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique.

(And her only thirty-one.)

I can’t help it, she said, pulling a long face,

It’s them pills I took, to bring it off, she said.

(She’s had five already, and nearly died of young George.)

The chemist said it would be all right, but I’ve never been the same.

You are a proper fool, I said.

Well, if Albert won’t leave you alone, there it is, I said,

What you get married for if you don’t want children?

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Well, that Sunday Albert was home, they had a hot gammon,

And they asked me in to dinner, to get the beauty of it hot—

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

HURRY UP PLEASE ITS TIME

Goonight Bill. Goonight Lou. Goonight May. Goonight.

Ta ta. Goonight. Goonight.

Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night.

In this fragment of verse drama, Eliot takes up the dramatic form in which Shelley, Tennyson, and Browning had dabbled in the nineteenth century and entirely renews it. Some readers, it is true, might find the renewal distasteful. Eliot’s post-war cockneys treat the procreative gift, after all, not as something involving the Creator or what might be the creature’s relation to the Creator but a “good time,” unwanted children, and abortion. Nevertheless, though not all of us might now end our evenings in public houses, this fallen world is our world. It is also a world that Eliot has one of his characters describe with a certain elegant succinctness in another of his verse dramas, Fragment of an Agon (1927):

Birth, and copulation, and death

That’s all the facts when you come to brass tacks …

Copulation of this bleak variety figures rather strikingly in The Waste Land. There, Eliot describes the reception of a male guest by a young working woman—a typist—at home in her flat, a reception which the poet stage-manages from the standpoint of Tiresias, the Theban seer who acts as a kind of tragic chorus of one.

At the violet hour, when the eyes and back

Turn upward from the desk, when the human engine waits

Like a taxi throbbing waiting,

I Tiresias, though blind, throbbing between two lives,

Old man with wrinkled female breasts, can see

At the violet hour, the evening hour that strives

Homeward, and brings the sailor home from sea,

The typist home at teatime, clears her breakfast, lights

Her stove, and lays out food in tins.

Out of the window perilously spread

Her drying combinations touched by the sun’s last rays,

On the divan are piled (at night her bed)

Stockings, slippers, camisoles, and stays.

I Tiresias, old man with wrinkled dugs

Perceived the scene, and foretold the rest—

I too awaited the expected guest.

He, the young man carbuncular, arrives,

A small house agent’s clerk, with one bold stare,

One of the low on whom assurance sits

As a silk hat on a Bradford millionaire.

The time is now propitious, as he guesses,

The meal is ended, she is bored and tired,

Endeavours to engage her in caresses

Which still are unreproved, if undesired.

Flushed and decided, he assaults at once;

Exploring hands encounter no defence;

His vanity requires no response,

And makes a welcome of indifference.

(And I Tiresias have foresuffered all

Enacted on this same divan or bed;

I who have sat by Thebes below the wall

And walked among the lowest of the dead.)

Bestows one final patronising kiss,

And gropes his way, finding the stairs unlit . . .

That Tiresias was blinded by Hera after claiming that women drew more pleasure from the sexual act than men makes his witness here peculiarly ironic: No one could infer such a claim from Eliot’s bored typist. Tiresias’ transvestitism—a mark of the shaman—is another apt twist, reflecting as it does the sexual anarchy exhibited by the poem. Then, again, Eliot certainly wished to have his readers recall that the clairvoyant seer figures in Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, where he recognizes before any of the other characters that the reason why Thebes has been burned to the ground—turned into a waste land—is because Oedipus lay with his mother.

Too many upbraid the 1960s for landing us in the sexual dystopia that now coarsens and degrades so many aspects of our moral life. As the foregoing shows, Eliot knew the evil was abroad long before what became known as the Sexual Revolution arrived on our doorsteps. The critic in him may have got the ruling of the Lambeth Conference (1930) terribly wrong— crediting the Anglican bishops’ relaxation of their ban on contraception with bowing to what he called the “facts of life”—but the prophetic poet knew otherwise. When he chose for the poem’s epigraph a passage from the Satyricon of Petronius, in which the Sibyl is asked what she wants and she responds, “I want to die”—he gave the world a chilling augury of our own culture of death. In the poem’s first section, “The Burial of the Dead,” Eliot’s Dantescan lines: “A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many/I had not thought death had undone so many” make the augury clearer still.

Yet another of Eliot’s prophetic twists can be seen in “The Fire Sermon” or third section of the poem.

The nymphs are departed.

And their friends, the loitering heirs of City directors;

Departed, have left no addresses.

By the waters of Leman I sat down and wept . . .

Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song,

Sweet Thames, run softly, for I speak not loud or long.

But at my back in a cold blast I hear

The rattle of the bones…

Here, alluding to Edmund Spenser’s “Prothalamion” and Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress,” Eliot shows how the culture of death corrodes not only the desire central to the carpe diem poem but the festive expectancy of the bridal day. Exiled from the land of our desire, we know only the groaning of the prisoner. Indeed, exile is one of the poem’s fundamental preoccupations. While the “waters of Leman” refer to the Lake of Geneva (Lac Léman), beside which Eliot finished his poem, it is also an echo of the “waters of Oblivion” in Psalm 137 in which the Israelites decry their Babylonian exile.

Seeing how the betrayal of the procreative gift deadens life, we can begin to understand how radical our need to know, love and serve our Creator is. If we refuse to acknowledge that need, life does become a matter of mere “Birth, and copulation, and death.” Conversely, if we recognize the need, as Eliot recognized it, we enter a new life. We can also rejoice in the ending of Ash-Wednesday (1930), Eliot’s poem of conversion, which, echoing the Anima Christi and Psalm 102, serves as a kind of coda to The Waste Land:

Even among these rocks,

Our peace in His will

And even among these rocks

Sister, mother

And spirit of the river, spirit of the sea,

Suffer me not to be separated

And let my cry come unto Thee.