Rediscovering that Rare, Beautiful Thing: The Summer Argument

It was the perfect mid-summer headline: “Terror as Amusement Park Ride Unable to Stop.” Our worst nightmare is not strange aliens, nuclear annihilation, the bizarre, or the fantastical. It is that we are doomed to live in the small space of our own vision; condemned to remain forever on the amusement park ride of our choice.

Mercifully, most of us come to see that life is not an amusement park ride. It is often not fun, but it is always meaningful, and finding the meaning drives us. Viktor Frankl was right. More than anything else—more than safety and security, ease, amusement, and pleasure, power and sex—we long for meaning.

The summer holidays are holy days in much the same way that hunger is a homage to food. The disengagement from work allows us to relax and amuse ourselves. However, come August, we can experience a stickiness of Being, a simmering self-loathing, a low-boiling existential crisis. And this is as it should be. Dissatisfaction impels us.

But while our culture may accept dissatisfaction as an engine of creativity and industry, it takes a low view of deeper currents of internal dissonance and irony. The well-adjusted are always having a good day and almost no one smokes anymore. Perhaps more than any other age, we have been drawn up by the monistic optimism of progress. We are all racing forward.

But this is a betrayal of truth. Dialectic is the habit of mind that animates both Jerusalem and Athens, faith and reason. At their most fundamental level, both theology and philosophy are non-dogmatic, non-ideological, groping in the dark. They are discussions animated by counterpoint. Both Jewish and Christian theology begin and leave off with the recognition that God is at once knowable and beyond knowing, that God cannot be contained in a horizon of understanding. Within the word philosophy itself, is the recognition that wisdom, while it can be sought and loved, will finally remain out of reach.

The easy goods of summer are time, sunshine, and warmth. The season’s great gifts, though, are boredom, shade, and the cool of the afternoon. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is the perfect summer play, crackling with conflict and revelation like a thunderstorm, sufficiently disturbing to right-size our own disquiets—like a good friend whose troubles are worse than our own. Many people love spring best, and who could fault them? In spring the whole world radiates the fresh beauty of young children. But hot, parched summer ripens the fruit of Being in all of us.

In summer, we get together with family members, some of whom may have left the faith. It is reassuring when we see that the faith has not left them. Honesty owns up to the inexorable passage of time, the shortness of life, and the hollow triumphs and disappointments of the world. But these bitters are also sweet hungers, which pay homage to the Bread of Life. The longing for God growls like an empty stomach.

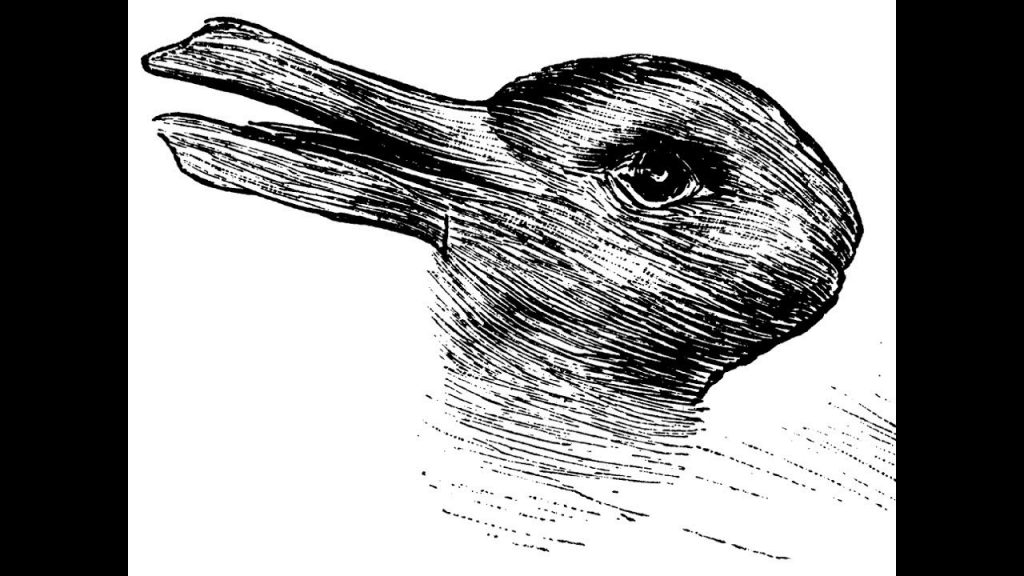

If the infection of the age has not paralyzed your family, you may still enjoy some good arguments, but these are on the endangered species list. One way to gently ease a family member toward good argument is to reveal some part of your own internal dissonance. Epistemology may seem arcane—and I don’t recommend using the word—but everyone puzzles over why reasonable persons may view the meaning of life differently. Ludwig Wittgenstein used the (now famous) duck-rabbit figure to illustrate the problem of aspect, or “seeing as,” perception.

Someone looking at the image may first see a duck or a rabbit, but most people can easily flip back and forth. Obviously, the image on the page has not changed and neither has the person’s retina. In a short but interesting article, philosopher Stephen Law points to the importance of “seeing as”:

For example, when I see a pair of scissors, I don’t see them as a mere physical thing—I immediately grasp that this is a tool with which I can do various things. Seeing the object as a pair of scissors is something I do unthinkingly and indeed involuntarily.

On the other hand, someone entirely unfamiliar with the concept of a pair of scissors not only won’t but can’t see the object that way.

We see what is useful to us, more than the thing in itself. Seeing is projecting out our engagement. We are always part of the picture. Seeing is encompassed by Being. Law goes on to give examples of how we might hear the opening bars of a tune and be able to carry it forward, or recognize a sequence like 2,4,6 . . . and be able to extend it. Our thinking relies upon our perceptions, but our perceptions are subsumed in an architecture of understanding.

The beauty of thinking about such things together is that we are not just analyzing others, we are analyzing ourselves. Together, we step outside of our feelings, roles, and habitual postures. Together, we enter the world of ideas, where maybe we can have a good-will argument.

In court, tradition has lawyers on opposite sides refer to each other as “friend,” not ironically—even as the parry and thrust seeks the mortal wound—but in deep earnest, in the hope that if each does his job well, truth will win out. Important questions, such as those concerning the existence of God and our obligations to protect the lives of the vulnerable, may be rooted in aspect perception, which may in turn be rooted in seeing as part of Being. We can’t help but believe in God and feel a deep obligation to protect the vulnerable when we recognize that to Be is to Love. And there is no better place to warm to that eternal truth than in summer arguments with family.