THE FAMILY ROE: AN AMERICAN STORY

THE FAMILY ROE: AN AMERICAN STORY

Joshua Prager

(W.W. Norton and Company, 2021, hardcover, 655 pages, $35)

Reviewed by Maria McFadden Maffucci

_______________________________________________

Norma McCorvey, the “Jane Roe” of Roe v. Wade, died in 2017 at the age of 69. In 2020, after the documentary AKA Jane Roe was released, the liberal media triumphantly declared her celebrated conversion to the pro-life cause a “con.” From Michelle Goldberg in the New York Times (May 29, 2020):

In the documentary’s final 20 minutes, McCorvey, who died of heart failure in 2017, gives what she calls her “deathbed confession.” She and the pro-life movement, she said, were using each other: “I took their money, and they put me out in front of the cameras and told me what to say, and that’s what I’d say.”

But the headline—that she “did it for the money”—was itself a con, according to the man who spent a full decade in pursuit of the truth about Norma McCorvey. In his hefty new book The Family Roe: An American Story, Joshua Prager writes of Norma’s “deathbed confession”:

Norma had not, in fact, been paid to become pro-life. She’d simply been paid to give speeches after her conversion—just as she’d been to speak before it. Despite the headlines, she’d said nothing to the contrary. The filmmaker, however, had asked Norma if her pro-life turn had been “an act,” and Norma answered yes—one more improvisation in a life that had for so long been a sort of performance art (p. 469).

Indeed, writes Prager, Norma’s life story “resisted rendering”:

She had cloaked it in lies; her two autobiographies were fiction. Among much else, she wrote that a nun raped her, that a cousin raped her, that a trio of strangers raped her, that her husband beat her, that her mother kidnapped her child, that she went to an illegal clinic to get an abortion, only to find it caked in blood, . . . that she helped to perform unsafe abortions. None of it was true (p. 483).

When once I pointed out to Norma that she had just lied, she’d replied with a smile: “They’ll take anything you say.” Norma enjoyed telling stories (p. 470).

The one truth about Norma, writes Prager, is that “she had been forced by law to birth a child she did not want.” He recalls that after learning in 2010 that “Roe had been decided too late for Norma to have an abortion,” he “wondered about the baby she’d placed for adoption forty years before” and decided to look for him or her (p. 3). It was “Baby Roe” who led Prager to write this book.

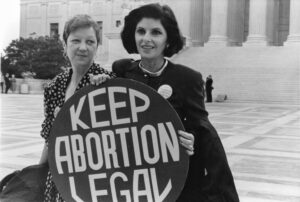

Lorie Shaull, photo. Norma McCorvey, left, with her attorney, Gloria Allred, outside the Supreme Court in April 1989, where the Court heard arguments in a case that could have overturned the Roe v. Wade decision.

His interest spread to all of Norma’s children, three daughters, each adopted by a different family. Over the course of his investigation, Prager not only finds “Baby Roe,” but reunites her with her family—partially. Baby Roe herself, Shelley Lynn Thornton, refused to meet Norma, her biological mother, face to face. (Shelley has only recently been “outed”; her identity was revealed in September 2021 when The Atlantic ran an adapted selection from Prager’s book.)

By doggedly tracking down and meeting Norma’s family and friends, and spending time with Norma herself, Prager surely gives us the most accurate picture we will ever get of this complicated figure. He also becomes part of the story: Norma’s three daughters, “delighted that I had brought them together,” invited him to important occasions “and kept in frequent communication.” Prager was privy to the most intimate details of Norma’s final struggles and, along with her daughter Melissa, was present at her death.

From his interest in the “Roe” family, Prager became hooked on the wider story: movement leaders on both sides of the issue whose lives intersected with Norma’s, the 1973 Supreme Court decision itself, and the issue of abortion in America—thus the size of this book! While the reader will “meet” many persons on both sides of the debate, Prager decided to profile “Three Texans” (Part II) in depth: Linda Coffee, the attorney who argued the Roe case with Sarah Weddington; Curtis Boyd, an abortionist since pre-legal days who currently performs late-term, partial-birth abortions in New Mexico; and Dr. Mildred Jefferson, who was the first president of the National Right to Life Committee. While people were familiar with these figures, Prager writes, even “if they knew something of their work, they knew next to nothing of them” (p. 481).

That was my experience with Mildred Jefferson. As someone who has been in the pro-life movement for most of my life, I’ve admired Jefferson as a pro-life hero—and trailblazer: She was the first African-American woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School. However, I had no idea of her troubled story, details of which Prager uncovered through her papers at Harvard, her FBI file, divorce record, and ex-husband, “sources it took me years to find” (p. 482). Jefferson’s life was one of contradictions: Because of the racism and misogyny she’d experienced, she vowed never to have her own children. She was also a secret but dangerous hoarder, something that contributed to the break-up of her marriage. But her opposition to abortion was absolute. Though he never met Jefferson, Prager seems to have become especially attached to her story, writing about her with respect and compassion.

Prager said in a television interview that his aim was to humanize the story of Roe, and I’d say he does: Abortion and pro-life advocates alike are described in the context of their personal stories—with warts galore, but also with an understanding that real people aren’t one-dimensional. (Having said that, the chapter on Curtis Boyd, presented frankly yet with no palpable moral disgust at Boyd’s zeal to do later and later abortions, I found hard to stomach.) Norma’s own story is sad from the beginning: persistent poverty, lack of education, abuse, alcoholism, depression. It’s clear that she was used by some on both sides of the abortion issue, but she was all too willing to be used if it meant something better for herself. Despite obviously having had sex with men, Norma was a lesbian; her most lasting relationship was with a woman, Connie Gonzalez—but she would go on frequent sexual adventures and her treatment of those who did care for her was sometimes callous. As for what she really thought about abortion, the best guess is she was ambivalent, at times depressed over her role; at times supportive of a woman’s choice.

Joshua Prager says he is “pro-choice” but “not an advocate . . . I am a journalist. And writing this book, I strove to be as sympathetic to the pro-life as the pro-choice” (p. 480). Overall, he does a commendable job, though there are glaring exceptions. He gives short shrift to the Catholic Church’s comprehensive and rich teaching on human life and sexuality, which intelligently informs its position on abortion. He mentions St. Augustine’s doubts about abortion being “homicide” before “quickening,” but he neglects to add that St. Augustine (as well as the Church) regarded abortion at any time during pregnancy as a serious sin. More importantly, instead of acknowledging the Church’s scholarship, its teaching about the dignity of each human being, and attention to the developing science of embryology, he intimates (pp. 39-40) that the eventual position of the Church on abortion was arbitrarily decided. For such a massively researched book—the notes alone take up over 100 pages—the Catholic Church’s solid stance in opposing abortion— and Christian pro-life scholarship in general—is given inadequate attention. Similarly, Prager rejects out of hand any claims that abortion has negative health consequences for women. For example, he writes there is a “nonexistent link between abortion and breast cancer” (p. 357) and that abortion has “no more risk to the psychological health of a woman than pregnancy or birth” (p. 440). Yet there are scores of women, doctors, and scientists who disagree. He might have included in his Notes a reference to the 2015 documentary Hush, where independent filmmaker Punam Kumar Gill, herself pro-choice, interviews experts across the ideological spectrum and concludes that women are being denied important health information because of the politics of abortion. Prager’s glib, abortion-has-no-negative-effects-forwomen attitude is out of place in a book that purports to examine the massive effect legalized abortion has had on so many aspects of American life.

These caveats notwithstanding, The Family Roe is an eminently valuable read for anyone who wants to understand the history of the Roe v. Wade decision—and its tragic aftermath.

______________________________________________________________

Original Bio:

Maria McFadden Maffucci is the Editor in Chief of the Human Life Review.

is the Editor in Chief of the Human Life Review

is the Editor in Chief of the Human Life Review