Murders in Kansas; Marked for Life

The mid-to-late fifties were a good time to grow up in Garden City, Kansas—a town of 10,000. My mother never lacked love, energy, dreams, and the most encouraging words. My father modeled a work ethic, held us accountable, and shared his wisdom, including how to be faithful fans of Kansas State football and basketball teams. My younger brother, mis-nicknamed “little Bruce,” was taller and more athletic than his older brother.

During these years I was well acquainted with First Methodist Church and its Sunday School. With neighborly families and close friends. Public school classes conducted by competent, caring teachers whose students were eager to learn. There were scout campouts on the prairie. Friday nights at the skating rink. Saturday mornings at the bowling alley. Saturday afternoons at the movies. Long, adventuresome hikes into the country or down by the Arkansas River. Pick-up football and basketball games with the guys. It was a good time and a good place to live. For this, I thank God.

One Sunday morning in mid-November of 1959, my family and I put on our “Sunday best” (attempting to make the hair above my forehead stand up, I smeared on some “butch hair wax”). Dad drove us less than the mile to church in our family car. Seated in our predictable pew in the sanctuary of First Methodist Church, we watched the weekly routine begin to unfold. Except this week what followed was not routine.

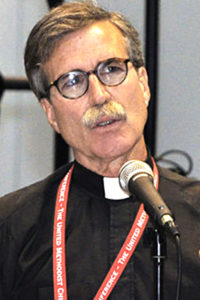

The pastor stepped into the elevated pulpit. With emotion in his voice, he announced that a terrible crime had been committed against four members of our church—Herb (48) and Bonnie (45) Clutter, and their children Nancy (16) and Kenyon (15). The Clutters lived in a house in the country—a few miles west of Garden City and just east of a village called Holcomb. The pastor then told us that the night before, the Clutters had been senselessly murdered. Their bloodied bodies were discovered earlier that morning. Local law enforcement had been contacted and he, as the Clutters’ pastor, was summoned to offer prayer at the scene of the crimes. After reporting this awful news to us, the pastor prayed to God for mercy and justice. Then, unable to continue, he canceled the Service of Worship. For a then-fourth grader, a canceled worship service would be something to remember for a lifetime.

The murderers turned out to be Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. While serving time at the Kansas State Penitentiary in Lansing, Hickock and Smith had heard a rumor from a fellow prisoner that the Clutter house near Holcomb had a safe containing thousands of dollars. As it actually happened, when the two subsequently broke into the Clutters’ house, they found no safe and only fifty dollars in cash. But having promised each other to leave no witnesses at the scene, Hickock and Smith shot-gunned the family and sped away into the night.

The Kansas Bureau of Investigation (KBI) played an important role in the criminal investigation. Putting together pieces of evidence (including the prison rumor), KBI agents identified, searched for, found, and arrested Hickock and Smith. They were charged, jailed, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to death by hanging. In 1965, they met their end at the end of a rope.

Truman Capote, who in the late 1950s wrote for The New Yorker, read about the Clutter murders just days after they had been committed. He and his assistant, Harper Lee (who later wrote To Kill a Mockingbird), traveled to Garden City and together began researching his next book. Their efforts led to the 1966 publication of In Cold Blood, which has been called the first “non-fiction novel.”

The film In Cold Blood was released in 1967. Capote, a 2005 movie, covered the Clutter family and their murderers, and the author’s experience writing about them. Family members and friends who lived in Garden City at the time of the killings have communicated on occasion about the horrifying loss of the Clutter family. Books, television programs, movies, and newspaper and magazine articles about the Clutter-Capote nexus still appear every so often, and we talk about them. Thus has this crime been woven into our memories, our minds, our lives.

Perhaps that is one reason that the Gospel of Life is so significant to this clergyman from Kansas. At the age of nine, the murder of the Clutter family burned into my heart and mind that every human life is precious. Every life deserves the chance to exist, to develop, to flourish, to glorify God, and to die in peace. Furthermore, at that tender age, from this terrible crime on the high plains, I discovered that there is something unspeakably and viciously wrong about the powerful destroying the weak. Perhaps the murders in Kansas marked one youngster—and maybe others—to defend unborn children—the weakest among us.