Closed Clinics and “Reduced Access” Save Lives

In recent years, abortion advocates have finally begun to admit that laws protecting the interests of unborn babies and their mothers may have closed some clinics*; however, they continue to assert that these laws have had minimal impact on abortion rates. At most, they say, this may have kept a few mothers from having abortions, but the more significant impact was in pushing the rest of the women to delay their abortions because of the need to travel great distances to obtain later, riskier, and more expensive abortions.1

Many of these claims were put to the test in 2011 with the passage of legislation in Texas imposing limits on the disbursement of family planning funds and in 2014 with the imposition of basic safety regulations on abortion clinics. Together, some say, these restrictions were responsible for closing half of the abortion clinics in Texas.

What was the real impact of that legislation?

There is a stronger correlation between the number of clinics and the number of abortions than abortion advocates acknowledge. Multiple factors may play a role,2 but the past four-plus decades since Roe clearly show that the number of abortions has risen when the number of “providers” increased—and has dropped once the number of clinics, hospitals, and private abortionists declined. The gravity of this situation for the abortion industry is apparent from their multi-pronged effort to boost the ranks of abortion providers and keep the industry going. Consider their determined legal challenges to safety regulations they believe are closing many of their clinics,3 and their coordinated media campaign complaining about closed clinics and the distance women have to travel to obtain abortions.4 Consider also the explicit focus of their efforts to expand abortion education at America’s medical colleges, as they seek to replace aging and retiring abortionists.5

Attempts to do more with fewer personnel are behind the nationwide effort to build giant regional mega-centers, where a handful of doctors, nurses, or physician assistants can handle a large volume of abortion cases;6 another strategy is to gain government authorization for at-home do-it-yourself abortions managed by telemedicine, with pills delivered by mail.7

All are part of the industry’s efforts to boost abortion “access”—to bring abortion to communities where it is not currently available, communities where there was insufficient demand to sustain a clinic or where residents decided, implicitly or explicitly, that they didn’t want or need an abortion clinic in their town.

The abortion industry’s concern about access is well founded, because statistics consistently show that fewer clinics usually mean fewer abortions. And thus more lives are saved as a result of those policies and conditions that close the clinics and thin the ranks of abortionists.

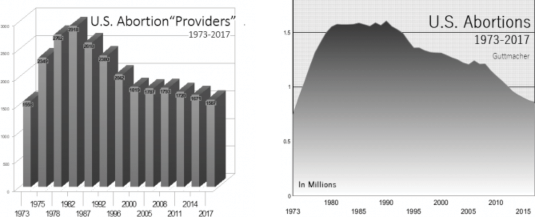

Go back 30 or 40 years and it is easy to see the correlation between the number of abortion clinics and the number of abortions (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 below).8 Once abortion was legalized, the number of abortion providers (a designation that includes clinics, hospitals, and private doctors’ offices performing abortions) soared, reaching a high of 2,918 in 1982. Not surprisingly, several abortion measures peaked about this time.

A Historical Connection

Abortions Fall after Number of Providers Drops

Annual abortions first climbed over 1.5 million in 1980 and hovered there before posting an all-time high of 1.6 million in 1990. Abortion rates (the number of abortions per thousand women of reproductive age) hit their peak earlier, in 1980 and 1981, at 29.3 per thousand. The abortion ratio—the number of abortions for every 100 pregnancies ending in abortion or live birth (as defined and measured by the Guttmacher Institute)—peaked at 30.4 in 1983.

As the number of providers fell, so did abortion indicators. Raw abortion numbers took a bit longer to begin falling, but abortion rates and ratios began to drop almost as soon as the number of providers did.

The number of abortions fell below 1.5 million for the first time in a dozen years in 1993 and never hit that mark again. This was just a year after Guttmacher showed the number of providers falling to 2,380. By 1996, when the number of providers had fallen to 2,042, the number of abortions was at 1.3 million. In 2001, the year after the number of providers dropped to 1,819, the number of abortions dropped into the 1.2 million range.

Though (owing to the addition of chemical abortion to many new practices) the decline in providers was somewhat more modest for the next two decades, the number of abortions continued to fall, hitting 1.15 million in 2009, 1.06 million in 2011, 0.96 million in 2013, dipping just under 0.9 million in 2015, and finally sinking to 0.86 million in the most recent Guttmacher report for 2017, when Guttmacher found just 1,587 “abortion providing facilities.”

Abortion Rates and Ratios More Responsive

Abortion rates and ratios seem even more sensitive to “provider” changes, falling almost immediately when the number of abortionists declined.

When the number of providers dropped in 1987, so did abortion rates and ratios, by 6.3 percent and 4 percent respectively. By 2000, when the number of providers had dropped by about a third from its 1982 peak, the abortion rate had fallen 26 percent, to 22.4 abortions per thousand women of reproductive age, and the abortion ratio had dropped 18.3 percent, to 24.5 abortions out of every 100 pregnancies ending in abortion or birth.

In the latest Guttmacher report, with just 1,587 providers in 2017, the abortion rate reached an all-time low of 13.5 per thousand, the lowest rate recorded since the court legalized abortion in Roe v. Wade in 1973 and a figure less than half what it was at the peak of 29.3 set in 1980 and 1981, when the country may have had its peak number of “providers.”

The abortion ratio, 18.4 abortions for every 100 pregnancies ending in abortion or birth, was also lower than it had been at any time since Roe, and well off the peak of 30.4 set in 1983, the year after Guttmacher showed the providers peaking.

A Favorable Feedback Loop

While historically it looks as if the drop in providers precedes the drop in abortions and that effect appears to extend into the future, there is also clearly some symbiotic symmetry in place, with reductions in the number of providers leading to reduced demand and then reduced demand leading to fewer clinics.

The takeaway here is that if there are fewer providers—fewer clinics, fewer abortionists—fewer women will seek abortions. If fewer women seek abortions, there will be less business to go around for abortion “providers,” inevitably leading more abortion clinics and practices to close. And that will in turn mean fewer women getting abortions, which will again cause more clinics to close, and so on.

While this is not the full story behind the massive drop in abortions over the past thirty years, it is clearly a major part of it.

What Happens When Clinics Close

This supply and demand dynamic is something to keep in mind when considering claims of abortion advocates about the effect of clinic closures, the distance women travel to obtain abortions, or the “need” for telemedical abortions. When an abortionist retires without a replacement, when a clinic closes rather than renovating in order to comply with new safety regulations, when a national chain consolidates several smaller clinics (perhaps with plans to build a large modern regional mega-center), the numbers will likely go down.

Some women may turn to different “providers,” try out the new clinics, order abortion drugs over the internet, or try the new telemedical chemical abortions if those are available in their state. A few will end up having later, more expensive, higher risk abortions. But some will forgo abortion, go ahead with the pregnancy, and give birth. The only question is how many will do so.

Statistics Show More Babies Survive

The idea that fewer abortion clinics will mean the birth of more babies is more than just wishful thinking or even a logical conjecture.

Three California economists who looked at the effects of the Texas legislation passed between 2011 and 2014 on abortion and family planning centers found not only that several clinics had closed (the authors stated that half the state’s abortion clinics had closed by 2015, though some closures may have been due to causes other than the legislation), but that abortion rates had declined by some 20 percent. More important, data from their analysis found that a “reduction in abortion access” (a reduction in the number and thus the density of abortion providers) in Texas correlated with a 3 percent increase in births.9

This is significant because, while the fall in abortion rates could be explained by women getting abortions out of state or attempting to self-administer an abortion, or even by increased use of contraception, an actual increase in birth strongly suggests that “reduced abortion access” had the effect of prompting a number of women to carry their children to term.

Looking just at the impact of distance to the nearest “family planning” clinic (though it is not specified, the implication seems to be that this is one offering abortion), the authors concluded that the lack of such a clinic within 25 miles is associated with a 1 percent increase in births.

Though the percentages sound modest, the actual numbers are impressive: 3 percent of the nearly 400,000 births to Texas residents in 2014 (Texas Department of State Health Services) would represent 12,000 more babies being born rather than aborted. Even a 1 percent increase would mean some 4,000 additional babies surviving.

The California economists did not go so far as to attribute the whole increase to limits on “abortion access,” but were willing to estimate that a significant number of the additional births (more than 3,200) were likely a result of legislation passed by the state.10

By any measure, thousands of unborn lives were saved.

Percentages Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Measuring birth rates against abortion rates is legitimate given the focus here, but the use of percentages can mislead us about the magnitude of the shift due to the relative size of the data fields.

Figures from the Guttmacher Institute show that 73,200 abortions were performed in Texas in 2011, but just 55,230 in 2014, a drop of 17,970 or 24.5 percent. This doesn’t adjust for population changes or the number of abortions that residents of Texas got in other states or that residents of other states got in Texas, but it does offer tangible evidence of the impact of clinic closings and other social or policy changes.

A 3 percent increase in births does not seem to be as big an effect as a 24.5 percent drop in abortion rates; however, because births outnumbered abortions in Texas by more than seven to one, the seemingly small size of the effect is an illusion.

As noted above, considered in terms of raw numbers, 3 percent more births in Texas in 2014 would represent about 12,000 additional babies being born. At the same time, a 24.5 percent drop in abortions during the same time frame meant nearly 18,000 fewer unborn babies being killed.

If those figures were determined to be actual, as much as two-thirds of the reduction in the number of abortions in Texas between 2011 and 2014 could have been because of women choosing to give birth to their babies instead of aborting them!11

Even if only 3,230 of those additional births were due to Texas legislation defunding family planning or regulating abortion clinics, as the California economists asserted, that alone would still represent 18 percent of the drop in abortions between 2011 and 2014, a substantial number of lives saved.

Increased Delay, Increased Risk?

Abortion advocates complain that one of the greatest travesties of these laws and policies limiting abortion “access” is that they cause women to delay their abortions, thereby increasing their cost and risk.

To assess this prediction, abortion advocates attempted to quantify the impact of pro-life Texas legislation on the timing of women’s abortions. Although the years and data are not precisely the same, researchers compared the number of abortions at 12 weeks or more (essentially second-trimester procedures) from the twelve months before (11/11 10/12) implementation of Texas’ House Bill 2 (HB2) legislation to another twelve-month period after HB2 had fully gone into effect (11/13-10/14). They found that the law had the effect of increasing later abortions by 907, from 6,813 to 7,720 per year, an increase of around 13.3 percent.12 Although the researchers continued to assert that later abortions were “safe,” they expressed concern about the higher risk of complications with these abortions.

The source they cite for this increased risk puts the risk of complications for second-trimester abortions at 1.47 percent, versus a risk of 1.26 percent for standard first-trimester vacuum aspiration abortions.13 The risk of a “major complication” (defined as a “serious unexpected adverse event requiring hospital admission, surgery, or blood transfusion”) for these later abortions was 0.41 percent.

Applied to the 907 additional women having later abortions identified in the earlier study, this means about 13.3 women facing complications with secondtrimester abortions versus just 11.4 of those women who would have encountered such a risk with a first-trimester suction abortion.** In essence, using their data, this means that perhaps two or at most three additional women in Texas had complications in that year because of the law, with the likelihood that these complications would not have qualified as “major.”

Thus, it can be inferred from the data that these new restrictions on “abortion access” may have meant perhaps two or three additional women facing minor complications and a few more dealing with the increased hassle and costs of later abortions. However, data from the same set of Texas women tell us the policies that led to that outcome may very well have saved the lives of at least 3,200 and as many as 12,000 unborn children or more a year, which should weigh heavily in the assessment of those policies.

Lives Hang in the Balance

Stephanie Toti, the lawyer who challenged Texas’ abortion clinic safety measures before the Supreme Court in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt in 2016, argued that laws such as those the legislature passed in Texas actually had the effect of increasing risks to women’s health by pushing them to pursue later abortions.14

She won her case, and the Court gutted key elements of Texas’ abortion law requiring abortionists to have admitting privileges at local hospitals and requiring that their clinics meet the same safety standards as other ambulatory surgical centers. The majority opinion in that case, authored by Justice Stephen Breyer, concluded that the Texas law was responsible for the closing of half of the abortion clinics in the state, creating an “undue burden” for women seeking abortion.15

Since the case was decided, a few clinics have reopened in Texas and a couple of newer ones have been built (Kaiser Health News, 11/18/19). The consequence? The most recent data from Guttmacher shows abortions increasing in Texas in 2017, and data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control for 2018 and 2019 hint at increases in the years to come.

The majority in Hellerstedt took for granted that women’s inability to readily and conveniently abort their unborn children was a negative outcome, never balancing out the benefit that might accrue in unborn lives saved. Our evidence does appear to show that the laws and circumstances closing clinics may lead some women to travel further and have later, more expensive abortions, with perhaps a very few facing some increased risk of complication or injury. But it also shows the consequence of thousands of women forgoing abortion and giving birth to their children.

These are not women “stuck forever with a baby they do not want.” Diana Greene Foster, principal investigator for the infamous “Turnaway Study” that tracked a thousand women who sought but were “denied abortions,” found that five years after being “denied” abortion and bearing their children, only 4 percent of women were still wishing they could have aborted their child.16 The rest had come to terms with their situation and may even have come to cherish those children spared the abortionist’s knife. A child living rather than aborted is a good thing, and most mothers—even those who at one time thought abortion was the “choice” they wanted and needed—eventually come to believe so.

The proper assessment of any policy that closes clinics and reduces reliance on abortion as the solution to unplanned pregnancy must also count its considerable benefits. The assault on clinic safety rules, the building of new megaclinics, the promotion of telemedical and do-it-yourself abortions, the recruitment and training of new abortionists, the push to fund abortion giants—all are part of the effort to reverse this trend of closing clinics, to rebuild the industry and make abortion more “accessible.”

Hopefully, many of this country’s young mothers have found that this aggressive abortion-industry rebuilding campaign is one that they and their unborn children can well live without.

NOTES

1. Joerg Dreweke, “U.S. Abortion Rate Continues to Decline While Debate over Means to the End Continues,” Guttmacher Policy Review, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Spring 2014). Elisabeth Nash and Joerg Dreweke, “The U.S. Abortion Rate Continues to Drop: Once Again, Abortion Restrictions Are Not the Main Cause,” Guttmacher Policy Review, Vol. 22 (2019).

2. Randall K. O’Bannon, “Abortion Establishment’s alarm over clinic closings conveniently omits what is really happening and why,” NRL News Today, February 25, 2016. See also O’Bannon, “Issues rasied as the Supreme Court Considers Texas Abortion Law—Part 2: A Dying Business,” NRL News Today, March 9, 2016, at https:// www.nationalrighttolifenews.org/2016/03/issues-raised-as-the-supreme-court-considers-texas-abortionlaw-part-2-a-dying-business/, accessed 3/10/21.

3. While Elizabeth Nash and Joerg Dreweke argue in “The U.S. Abortion Rate Continues to Drop: Once Again, State Abortion Restrictions Are Note the Main Driver,” Guttmacher Policy Review, Vol 22 (September 18, 2019), www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2019/09/us-abortion-rate-continues-drop-once-again state-abortion-restrictions-are-not-main, that regulations are not primarily responsible for declining abortion rates, they do say that “there appears to be a clear link in many states between abortion restrictions—and TRAP [‘Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers’] laws in particular—and clinic closures . . .” Their failure to see the connection stretching back decades between declining numbers of providers and dropping abortions comes from failing to see how regulations from one state may impact its neighbors and the overall culture, leading to abortion drops across the board.

4. Benjamin P. Brown, “Distance to an Abortion Provider and Its Association with the Abortion Rate: A Multistate Longitudinal Analysis,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 52, No. 4 (December 2020). Brown claims that each additional mile of distance between a potential client and an abortion “provider” was associated with a 0.011 decrease in the abortion rate.

5. Ariana H. Bennet, et al., “Interprofessional Abortion Opposition: A National Survey and Qualitative Interviews with Abortion Training Program Directors at U.S. Teaching Hospitals,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, January 7, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1363/psrh.12162. Bennet and team note high levels of internal opposition to abortion training at U.S. medical schools and argue that “Interventions are needed that prioritize patient’s needs . . .”

6. How this works is spelled out in O’Bannon, “Fewer clinics in 2020, but Planned Parenthood performing more abortions, later abortions, than it was ten years ago,” NRL News, April 20, 2020, at https://www. nationalrighttolifenews.org/2020/04/fewer-clinics-in-2020-but-planned-parenthood-performing-moreabortions-later-abortions-than-it-was-ten-years-ago/, accessed 3/10/21. Key elements of the strategy are also revealed by sympathetic industry sources in Erin Heger, “The Strategy Behind Where to Build Abortion Clinics,” Rewire, October 11, 2019, at https://rewirenewsgroup.com/article/2019/10/11/thestrategy-behind-where-to-build-abortion-clinics/, accessed 3/10/21.

7. Ushma D. Upadhyay, et al., “Adoption of no-test and telehealth medication abortion care among independent abortion providers in response to COVID-19,” Contraception X, published online November

21, 2020, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7718446/pdf/main.pdf.

8. Abortion advocates acknowledge both drops but wish to argue that other factors may play a role in the decline. In theory, many elements can contribute to drops (or increases) in abortion. Population and demographic shifts—increases, decreases in population, an aging of the population of reproductive age, an influx of immigrants, migration between urban, suburban, and rural areas, etc.—can all play a part in not just the number, but the distribution of abortions. Some of that may have happened here, but general trends show population increasing, particularly among those groups having higher abortion rates (blacks, Hispanics), making this unlikely as a main cause of abortion or clinic declines. Anything impacting overall fertility, reducing or increasing pregnancy—contraception, abstinence campaigns, cultural or biological factors (e.g., sexually transmitted infections and diseases, social media’s reduction of in-person relationships) that make reproduction more or less likely—will also impact abortion rates. Increased and/ or better use of birth control is the explanation most frequently offered by abortion advocates. Though contraception may play some role in reducing pregnancy rates, experts admit this cannot fully explain the drop (see DG Foster, “Dramatic Decreases in U.S. Abortion Rates . . .,” American Journal of Public Health, December 2017). Laws or policies that encourage or discourage abstinence, birth control, childbearing, abortion, or family formation by regulating or funding any aspect of these can impact both the number of pregnancies and their outcome. That births have generally fallen in parallel to abortions leads many to think that contraception, and the use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) in particular, is the explanation for falling abortion rates, but this is not a neat one-to-one correspondence. Other factors besides birth control can reduce pregnancy (see above) and there are times over the past thirty years when births rose while abortions continued falling. It is worth noting that births in Texas were indeed up during the time period in question, and abortion advocates on the ground admitted that pro-life laws, rather than contraception, had a major impact. Dr. Daniel Grossman, an abortion advocate from the University of California San Francisco who did research on the impact of Texas legislation, told the Los Angeles Times (1/17/17): “In Texas I don’t think that the decline in abortion has been related to improvements in contraceptive use I think it has more to do with barriers to accessing abortion.”

9. Stefanie Fischer, Heather Royer, and Corey White in Working Paper 23634, “The Impact of Reduced Access to Abortion and Family Planning Services on Abortion, Births, and Contraceptive Purchases,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA (December 2017), p. 5. Document available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23634/w23634.pdf, accessed 4/19/21.

10. Fischer, Royer, and White, p. 35.

11. Though theoretically it is possible that, finding no clinic in the immediate area, some Texas women could have gone to clinics in neighboring states, statistics do not support this happening on a scale to account for sizeable declines in that state’s abortions. According to the Guttmacher Institute, abortions in Texas’ border states of Colorado (-1,550), Louisiana (-2,060), New Mexico (-530), and Oklahoma (-530) all fell by at least several hundred from 2011 to 2014, the period being discussed here. Only Arkansas and Kansas showed what appeared to be a temporary blip, increasing by 220 and 300 between 2011 and 2014, respectively (though the Centers for Disease Control, normally undercounting Guttmacher’s state totals, showed Kansas having a overall decrease of 557 between 2011 and 2014). However, the tiny increases in these two states are nowhere near enough to account for the nearly 18,000 fewer abortions performed in Texas in 2014 than in 2011. Some have argued that the reductions in the numbers of abortions have been offset by pregnant women, particularly those living near the border, having abortions at home using pills brought back from Mexico. Though it is conceivable that this may have occurred in some cases, it seems unlikely to explain all or even most of the drop. Advocates of abortion published studies that gave the impression that there was a sudden surge in attempted DIY abortions, but their actual data showed only that a certain, small percentage of women may have attempted (or simply investigated the possibility of) self-aborting at some point during the twenty or thirty years of their reproductive lives (see Randall K. O’Bannon, “Study does not demonstrate self abortions suddenly increased at the passage of pro-life law,” National Right to Life News, December 2015, p. 12 at nrlc.org/uploads/NRLNewsDec2015.pdf). And though many stories about self-managed abortions appeared in the wake of Texas legislation, accounts of these do-it-yourself (DIY) abortions with pills brought back from the border actually predate HB2 and Texas’ earlier family planning funding restrictions (e.g., Laura Tillman, “Southern Border Brings Easy Access to Abortion Inducing Drugs,” Brownsville Herald, 3/25/08). Even if a number of women turning to DIY abortion could explain some of the abortion decreases, it would still fail to account for the sudden increase in births that show up in Texas statistics at this same point.

12. Kari White, et al., “Change in Second-Trimester Abortion After Implementation of a Restrictive State Law,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 133, No. 4 (April 2019), pp. 771-779.

13. Ushma D. Upadhyay, et al., “Incidence of Emergency Department Visits and Complications After Abortion,” Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 125, No.1 (January 2015), pp. 175-183, at 177. We should note for the record that this lower rate of 1.26 percent was specifically for first-trimester aspiration abortions; first-trimester chemical abortions employing “medications” like mifepristone were found to have a complication rate of 5.19 percent, considerably higher than either those first-trimester aspiration abortions or those second-trimester or later surgical procedures. This should be kept in mind when considering the abortion industry’s efforts to promote telemedical or at-home chemical abortions as a substitute for in-clinic abortions.

14. Stephanie Toti, senior counsel for the Center for Reproductive Rights, argued against the Texas law, specifically making the claim that the closure of clinics would lead to more women having later, riskier abortions. According to the Official Transcript of Oral Arguments of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, argued March 2, 2016, before the Supreme Court, Toti said: “there is evidence in the record that following implementation of the admitting-privileges requirement, in the six-month period following, there was an increase in both the number and the proportion of abortions being performed in the second trimester. So by delaying women’s access to abortion, these requirements are actually increasing the risks that women face” (at page 22). Toti and her team were able to convince the court to overturn the Texas regulations.

15. This was disputed by Justice Samuel Alito, who, along with Justice Clarence Thomas and Chief Justice John Roberts, rejected the claim that this law imposed an “undue burden” and pointed out that several clinics closed prior to the law’s passage and may have closed for other reasons, such as earlier state funding cuts, the retirements of abortionists, or even reduced demand.

16. Diana Greene Foster, The Turnaway Study (Scribner: New York, 2020), p. 126. The 4 percent figure was likely inflated by women who allowed their child to be adopted. Five years out, 15 percent of those allowing their child to be adopted still wished they could have aborted, compared to just 2 percent of those who chose to parent.

_______________________

*As far as National Right to Life is concerned, the real issue is whether these clinics perform or facilitate abortions, not whether they are closed. If they ceased performing abortions, but continued to offer contraception and other services, as some may have done in Texas (Dallas Morning News, 3/21/16), they may have contributed to the abortion decline while remaining open. But because activists, studies, and the media have focused on clinic closings and used this as the metric to gauge abortion availability or “access,” and because closed clinics would obviously no longer be providing abortions, this is the measure that will be the focus of this report.

_______________________

**This assumes, rather charitably, that all first trimester abortions were surgical suction abortions with the lower risk rate, though we know that a considerable portion of these were riskier chemical abortions. We know that nationally, 90 percent or more of all abortions in 2011 were first-trimester procedures and that about a quarter overall were “early medication abortions” using abortifacients like mifepristone, which Upadhyay, et al. (note 13) found came with a considerably higher 5.1 percent complication rate. If these percentages held for Texas, 227 of the 907 women newly facing second trimester abortions in Texas in 2014 would have faced decreased risk in switching from earlier chemical abortions to later surgical abortions.

If it is the case that many of the 18,000 or so abortions that disappeared in Texas from 2011 to 2014 were chemical abortions, as Daniel Grossman testified in U.S. District Court in the lead up to Hellerstedt (at that point Whole Woman’s Health v. Lakey, Direct Testimony of Daniel Grossman M.D., filed 8/4/14, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, Austin Division), then the net result would have been not a decrease, but an increase in safety, for those women who would have had chemical abortions “forced” to seek second-trimester surgical abortions.

______________________

Original Bio:

Randall K. O’Bannon is Director of Education & Research at the National Right to Life Educational Trust Fund.